Look Up Glasgow

13 Jan 2014

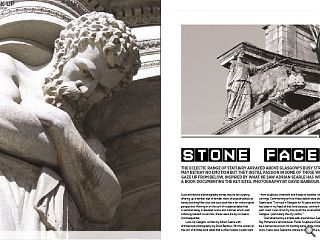

The eclectic range of statuary arrayed above Glasgow’s busy streets may betray no emotion but they instill passion in some of those who gaze up from below. Inspired by what he saw Adrian Searle has written a book documenting the key sites. Photography by David Barbour.

Look Up Glasgow, written by Adrian Searle with architectural photography by David Barbour, lifts the curtain on the sort of architectural detail that is often hidden in plain sight - from sculpture, ornament and friezes to weather vanes and carvings. Commenting on how these details were discovered Searle said: “I’ve lived in Glasgow for 16 years and the project has been in my head all that time because, coming from the east coast, I was struck by how lavish the ornamentation is in Glasgow - particularly the city centre. “

Overwhelmed by a simple walk around town Searle found Ray McKenzie’s seminal book, Public Sculpture of Glasgow, to be a tremendous boon for locating some of the more obscure work. It also gave Searle the chance to present the subject matter to a broader audience by ditching McKenzie’s somewhat dry and academic approach for a more personal collection that catalogues the more exuberant and esoteric of the follies. As Searle noted: “I was drawn to the interesting and the quirky – particularly figurative sculptures, the extraordinary figures that you see on tops of buildings. They have personality and give the building a feeling of being watched over benignly.“

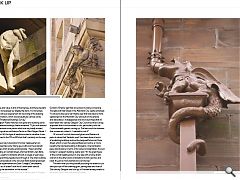

That quirkiness is best exemplified by one of only a handful of modern pieces in the book - a cat created by sculptor Calum Sinclair at 100 West George Street. The whimsical piece is so tucked away that it’s difficult to spot unless pointed out by someone in the know. Searle commented: “It harks back to the Victorian playfulness in terms of the use of sculpture to decorate buildings with a post-modern twist.”

It also shows that ornamentation isn’t exclusively a pre-war feature of city architecture, even if its practice has been drastically scaled back in pursuit of the rational and the functional. Is this something modern day architects should be re-embracing however? Searle responds: “I think it’s a case of everything in moderation, personally I love brutalism and modernist architecture but at the same time I think exuberance of any kind is to be applauded; whether it’s exuberance of minimalism or exuberance in ornament and decoration. That’s the beauty of the Scottish Parliament, where each building has its own integrity and playfulness. I guess it comes out in different ways these days and certainly function very much dominates that now with innovation in terms of space and light - but at the same time there’s definitely a place for ornament done well and tastefully in a tradition which stretches back hundreds of years.”

It is intended to follow-up the project by launching a smartphone app to act as a digital guide to allow locals and visitors to undertake their own walking tours, bringing the wider history and narrative of the work to life. Searle observed: “The feeling I get as an incomer to the city is that Glaswegians are only dimly aware of just how fabulous the city is architecturally, there is a perception that the east holds the jewel in the crown. Edinburgh is extraordinary and picture postcard perfect but architecturally it’s not nearly as interesting to me as the cornucopia of styles and approaches of Glasgow.”

Documenting this history is a race against time in many cases as the ravages of time, pollution and botched cleaning take their toll. Continued demolition is also denuding the city’s physical connections to the past; particularly in peripheral and disadvantaged districts beyond the relative affluence of the city centre. One recent egregious example is the loss of Springburn Public Halls, bulldozed last Christmas along with some stonking ornamentation.

Commenting on this loss Gemma Wild, heritage and design officer at the Scottish Civic Trust said: “If a building is being demolished, there is unlikely to be any requirement to remove and preserve ornamental features unless they have a strong significance and value in and of themselves, and there are plans for how to store/preserve/ display the items. It’s more likely that there will be a requirement for recording of the building prior to demolition, which would usually be carried out by RCAHMS Threatened Buildings Survey.”

Springburn Public Halls has now gone and outlining some other threatened buildings Searle remarked: “If you look around the city there are some pieces which are very badly eroded, such as a figurative motif above Sartis on West Regent Street. I don’t know if it’s the type of sandstone used or whether it was badly cleaned in the 70’s or 80’s but that’s certainly on the way out.

“Glasgow Gas Corporation’s former headquarters on Virginia Street has some Viking guys with enormous bandit moustaches which are also eroding badly. There’s another great building on Gorbals Street, a former British Linen Bank, which was used for a fantastic artwork a couple of years ago with a huge knitting needle stuck through it. The other building I’d be concerned about is the old Linen Bank building between the Chinese supermarket and Stow College (Cowcaddens). It’s lived in but it doesn’t look like it’s been taken care of, particularly the decoration on the outside.”

Another piece to have been lost in recent years is Douglas Gordon’s ‘Empire’ sign that once stood in a lane connecting Trongate with Bell Street in the Merchant City. Searle remarked: “It was done like a pre-war theatre sign that was back to front, signifying how the Merchant City was built on the empire and slave labour. It disappeared and one would hope that it’s been taken into care by Glasgow City Council but there’s a big argument that it should remain in situ, particularly with the Commonwealth games coming up. The fear would be however that someone’s nicked it - I wanted to nick it!”

Of course it’s not all doom and gloom and Searle is at pains to stress that ‘fantastic work’ has been done in terms of protecting buildings such as the Ladywell School on Duke Street, which is now the Ladywell Business Centre, or more recently the Olympia building in Bridgeton. One bombastic piece stands alone in terms of its scale and ostentation, the ‘just bonkers’ Clydeport building. Searle said: “It’s the great figure of the woman leading a bull on one side with a horse drawn chariot on the other and a child behind it with a portico and relief. It’s just so monumental and over the top.”

The next time you find yourself pounding the streets try to take your eye off the chewing gum, paving slabs and litter of 21st century Glasgow and look up, a Victorian fantasy awaits to be found – and it won’t be around forever.

|

|

Read next: New Urbanism

Read previous: Nigeria

Back to January 2014

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.