Is Architecture Dead?

18 Apr 2013

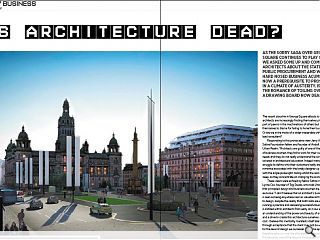

As the sorry saga over George Square continues to play out we asked some up and coming architects about the state of public procurement and whether hard nosed business acumen is now a prerequisite to prosper In a climate of austerity. Is the romance of toiling over a drawing board now dead?

The recent stooshie in George Square attests to the fact that architects are increasingly finding themselves playing the part of pawns in the machinations of others but are architects themselves to blame for failing to hone their business acumen? Or are we in the midst of a wider irreversible shift in their role as lead consultant?Responding to this provocative view Jerry Anderson, Saltire Foundation fellow and founder of Andell Architects, told Urban Realm: “Architects are guilty of one of the cardinal sins of business acumen, they fail to work for their customer’s needs and they do not really understand the concept, it is not covered in architectural education. Indeed many of them would struggle to define who their customers really are. There is a romance associated with the lonely designer up at midnight with the angle-poise light, toiling whilst the rest of the mortals sleep, as they concentrate on changing the world.”

These views were echoed by fellow Saltire member Lynne Cox, founder of Tog Studio, who told Urban Realm that principled design and business acumen are not mutually exclusive: “I don’t believe that an architect’s business acumen is seen as being anywhere near as valuable as their ability to design, despite the reality that both skills are essential in running a practice and delivering successful buildings. What is instilled within architects from early on in our education is an understanding of the power and beauty of architecture, and a drive to create this architecture ourselves whatever the cost. I believe this mentality manifests itself later in practice through acceptance that the client may not be willing to pay for the level of design we ourselves find to be appropriate, and therefore jobs run over the allocated time, losses are made, and this becomes one of the reasons the business of architecture is inefficient.”

Developing this theme further Cox went on to suggest many architects would rather not have to deal with the business side of being in practice at all and ‘would rather read a book on Chilean timber buildings than marketing of an evening’. Cox believes this to be a mistake however, observing: “… business strategy can be as innovative and dynamic as design. There are opportunities out there in the construction industry, underserved demographics, vacant sites, underutilised resources, and if more architects challenge the means by which they do business as creatively as they would challenge a project brief we may see more disruptive architectural business models emerging.”

Ruminating on the root cause of the professions decline Anderson rattled off a litany of perceived failings by architects, including an inability to ‘deliver what they say and when, lack of unity as a profession, cutting each other’s throats through ridiculous fee proposals, a weak and ineffectual professional body and a lack of leadership due to focusing on the wrong areas.’

As tonic for these ills Anderson suggests focusing priorities on three key areas; namely education (Anderson, himself a tutor, says most school’s ‘proverbial head is very much up their backsides with regards to making money’), a ‘useful’ professional body and an acknowledgement of clients financial priorities rather than simply focussing on design.

Building on these ideas Anderson ventured into the thorny wicket of suicide bidding, stating: “Fees should never be competitive against themselves, the profession needs to regulate like the legal and medical professions, where quality of service is what is sold, not the cost of it. If this cannot be done, which I guess they (RIAS) do not have the balls to do, then demand equity in added value for developments rather than fees, and becoming management contractors who control material and labour finance during the build phase or move into property development.”

The recession has been a boon in terms of new start-ups but Dele Adeyemo, co-founder of Pidgin Perfect told Urban Realm that he believed the architectural profession was ‘largely complicit’ in the excesses of that boom with many architects ‘guilty of focusing on the work, letting developers take the lead and losing sight of the bigger picture.’ Adeyemo said: “In the boom years of the noughties everyone was clamouring to make money out of buildings not just architects. Architecture was suddenly viewed as an investment fit for anyone regardless of your expertise. Everyone wanted to be a developer, buy to let, get a loan and get on the property ladder because ‘the market could only go up’. Now that the ‘good times’ are over and people are suffering through a long period of recession and economic stagnation there is clearly a real appetite right across society to focus on values of wellbeing and community. Because of this renewed public appetite, having a principled, ethical approach, has become ‘trendy’, which can be seen in the change in marketing of commercial enterprises - but people can see through that.

“There is a new wave of practices emerging, focusing on values like meaningful public engagement, working collaboratively with artists and designers to do this and employing fairer co-operative company structures, in essence they are doing things differently to make a difference. And you don’t have to set up your own practice, there are opportunities for graduates in architecture to make a real difference in local government, the civil service, design bodies and teaching.“

Anderson questions the long term viability of many new practices though, saying: “A graduate can’t get a job but his aunt wants an extension, it’s enough for him to decide, with a £1000 fee agreement, and his laptop, that, with a nice website, he is good to go.” Instead Anderson counsels: “Work for a building company for a year, understand finance, forget attic extensions, and forget Norman Foster. Forget trying to impress your peers, impress those outwith the profession. NEVER EVER, EVER WORK FOR FREE, EVER. NEVER DO COMPETITIONS FOR FREE, EVER. USE THE TIME SPECULATING ON THAT TO SPECULATE ON THINGS WHERE YOU HAVE CONTROL OVER THE RISK REWARD RATIO, LIFE IS TOO SHORT TO FANNY AROUND WITH COMPETITIONS THAT WON’T GET BUILT EVEN IF YOU WIN - No matter whether an architect reads this, they will be unable to comprehend the point, it’s just in their nature, tough love is needed unfortunately.”

Picking up on the root cause of these failings Cox singled out the education system for not imparting the breadth of knowledge required to stay afloat in today’s world, saying: “The skills that we learn for five years in university represent a fraction of the role we are expected to perform on leaving. I believe this has been damaging for talented students who are then hit with learning about the realities of construction in the final months of university. I believe there is an expectation, both from the student and the industry that after graduation the young architect will be sufficiently skilled to know how to go out into the world and build. In recent years I think this expectation has not been met. Postponing the learning of the day-to-day skills required to be an architect until the graduate is in practice I believe not only creates a sense of disillusionment for the graduate but has also helped to undermine the credibility of architects.

“I left university at the height of the recession, a decidedly dismal time for a new graduate to be phoning architecture practices looking for a placement only to be told that redundancies were being made and people with far more experience than me would be competing for work. What was equally uninspiring was the work being carried out by my peers who had managed to secure a job and were stuck doing something repetitive that they were not learning from. I took a side step and began working for A+DS on exhibition production, but there were others that were taking a far bolder step forward out of this dissatisfaction and established their own practice. Roots Design Workshop, Dress for the Weather, Pidgin Perfect, and Ice Cream Architecture all emerged at this time.”

Cox has two words of advice for anyone looking to achieve similar, saying ‘just start’, adding: “…what’s important is not so much what you don’t know but understanding what you need to learn to succeed. I think this is true, and certainly we found with Tog that there came a time where we just had to commit to doing our first live build project without knowing all the answers in advance, otherwise we couldn’t prove the concept and gain credibility. Another important lesson we learned was regarding focus and the importance of finding a niche in the market that only you can satisfy. This is a stronger position to hold than being all things to everyone and the work you choose to carry out will define the fundamentals of your business and what you are seen to stand for.”

Agreeing with the small is beautiful maxim Adeyemo added: “If you believe in principles and want to make a difference it can be difficult to achieve this in a large practice. If you join a big firm maybe one day when you have worked your way up the ranks of the agency it will be possible to make a bigger difference, but by the time you get there your values may have changed. But setting up your own practice allows you the freedom to throw your energy into responding to issues in your immediate context.”

Returning to the theme of start ups Cox made it clear she is under no illusions as to the challenges faced by this new breed of young, fresh-faced upstarts, lamenting: “The procurement system is prohibitive to small practices- there is too much expectation for design work to be carried out free of charge in order to secure a tender or enter a profile-raising competition. The reality is that larger practices have greater capital to absorb risk and it is more feasible for them to gamble time and money on such prospects. Small practices have the benefits of being lean and adaptable to working more efficiently, but they are also more fragile and need remuneration if they are to develop and survive. I think we should be encouraging creativity in small practices through commissions based on their achievements to date rather than asking them to submit work for competitions. This practice undermines the perceived value of design work for those who can least afford to do so.”

Architecture may not be dead then but if it is to avoid a spell on life support it has to change - and change fast. A confused sense of what an architect is has contributed to a diminution of the profession exacerbated by recession. Frustratingly most have an understanding of the issues and even ideas on how to turn things around. Be that Cox’s vision of a fit for purpose education system, or Anderson’s plea for the profession to embrace common sense business practices that any other industry would take for granted. Sadly what is lacking is a body willing to push these changes through.

|

|

Read next: Carbuncle Awards 2013

Read previous: Advocates Close

Back to April 2013

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.