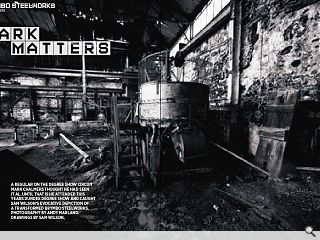

Brymbo Steelworks

21 Aug 2012

A regular on the degree show circuit Mark Chalmers thought he had seen it all. Until that is he attended this years Dundee degree show and caught sam wilson’s evocative depiction of a transformed Brymbo Steelworks. Photography by Andy Marland.

Drawings by Sam Wilson.

As one of a litany of lost British steelworks including Consett, Cargo Fleet, Irlam, Gartcosh, Corby, Dowlais, Ravenscraig – Brymbo’s story is characteristic. It began life as an ironworks, founded by John “Iron Mad” Wilkinson in 1792, after which the surviving blast furnace, known as Old No.1, was built. Brymbo grew during the early part of the 19th century, but when the Napoleonic Wars ended, the ironworks suffered a slump.

Its furnaces lay quiet for a decade, but Scottish capital saw Brymbo flourish again in the 1840’s. Robert Roy bought the ironworks, and commissioned his countryman Henry Robertson to develop the furnaces and sink a colliery nearby: by the following decade, Robertson saw that the industry’s future lay in steelmaking, and he began experimenting with Bessemer converters. Later, the Brymbo Steel Company developed steels for armaments and aircraft engines, and that specialisation saw it through hard times early in the 20th century. The company flourished, and layers of new buildings were superimposed over the 18th century ironworks.

After World War Two, Brymbo was run by the industrial conglomerate GKN, and huge new sheds were constructed to house electric arc furnaces, a cogging mill and a world-beating inspection department. Old No.1 and the warren of pattern shops on the eastern side of the site were overshadowed in every sense. The plant retained its unique place in the British steel industry, this time by melting specialist steels for hydraulic pit props and oil drilling bits – yet massive investment in 1980 wasn’t enough to save it, once Thatcher began destroying Britain’s industrial base.

After United Engineering Steels closed the plant 20 years ago, Brymbo became an industrial ruin in a rural setting. Retaining that unusual character is an important facet of Sam Wilson’s project, and helps to define what the site could become. The ruins of blast furnace bases hidden in the undergrowth at Brymbo resemble nothing so much as Francis Towne’s watercolours of the Baths of Caracalla: it emphasises that the remains of the industrial revolution are to us what the ruins of Rome were to previous generations.

The Adaptive Re-use Studio of the Masters Unit at Dundee School of Architecture is right on the money in pointing students towards restoration rather than newbuild, because that’s where much of the profession’s work lies at the moment, and Wilson’s Masters year was spent developing his interest in derelict industrial places into an architectural approach, with the dual inspirations of Christopher Alexander’s “Pattern Language” and the pattern-making which took place in Brymbo’s foundry mould shops.

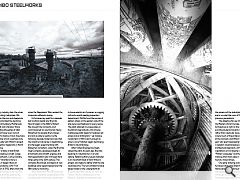

One early drawing evokes the blast furnaces which once lined the Rhine-Herne canal, establishing a scale and atmosphere which is characteristic of Volklingen or Zollverein in Germany. Those are huge industrial sites which have been stabilised and preserved, rather than over-restored. The Germans do industrial archaeology particularly well, and Wilson’s scheme is in that tradition, rather than the invasive adaptation at Wilkinson Eyre’s Magna (Templeborough steelworks) or the wholesale destruction of Ravenscraig during the late 1990’s.

The programme at Brymbo consists of three parts: a Blueprint Archive, with revolving cylindrical towers which house scrolled-up drawings; a Centre for Innovation and Development, to pass on heritage skills such as foundrywork to a new generation of artisans; and an Industrial Heritage Unit, to make components using Brymbo’s archive of patterns and hence generate income for the preservation of the remainder of the site.

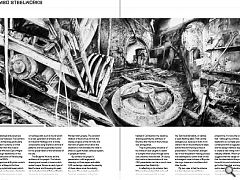

The Blueprint Archives are the emblems of this project. The historic drawings are housed in towers which evoke Cowper Stoves, an early type of blast furnace, and the epicyclic gears set inside them hint at Michael Webb’s scheme for a house based on the Wankel rotary engine. The constant rotation of the archives mirrors the steady progress of the mill rolls, and the trains of gears which drove the steelwork’s mills translate into what in effect is a giant Kardex carousel system, in perpetual motion.

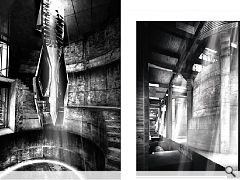

By contrast, the project’s presentation, with large pencil drawings on Rives paper and subtle CAD renderings, captures the serenity of these places once the industry has gone. The models were built in AutoCad, rendered in V-Ray then treated in Combustion: the resulting drawings portray the calmness of Brymbo after the fire in the furnaces was extinguished.

They’re particularly evocative of the motes of dust caught in a beam of sunlight which slices through some vast, shadowy machine hall. Of course, they’re also a demonstration of how CAD presentation can be so much more expressive than SketchUp...

In reflecting on his scheme, Sam Wilson acknowledges that some will dismiss it because it fails to meet the Technical Standards, or betrays a weak flashing detail. That’s a little disingenuous, because in truth it will stand or fail on the architectural ideas behind the shimmering surface of presentation. The scheme’s strength lies in how the pattern-making process was developed to confer order on the extravagant visual richness of Brymbo: the cogs, cranes and crucibles which litter the site.

My own view is that the scheme is a clear diagram carved from a complex site to accommodate a simple programme. It’s none the worse for that – although by contrast, a modern steelworks is a complex process contained within a huge plain shed, and the design methods deployed to create a new rolling mill would be radically different. Wilson presciently suggests that the design isn’t complete, that the ideas behind the project will live with him and continue to evolve. I’d go further than that, and suggest that such a keen eye for industrial heritage can provide insight and nourishment throughout your entire career.

|

|

Read next: Sculpture

Read previous: Golspie Street

Back to August 2012

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.