Making

4 Aug 2012

Paul Stallan of Stallan-Brand finds his work as an architect aided by a passion for paint and model making and has produced a prodigious body of work from his garage workshop. Here Stallan outlines the source of his creativity - his means of making.

As an architect I enjoy exploring visual form through painting and making objects. I also spend a lot of time making collages which I have always considered a very immediate and playful way to both explore and discover ideas. This twin preoccupation of studying artistic composition and exploring more conceptual art is complementary. For example, the strength of a drawing or an artworks concept and its formal composition are separate but if each is successful the art is more profound. Architecture is no different.

Importantly for me, the process of constructing a composition in paint or timber has direct parallels to some of the mental processes you go through as an architect making architecture. Obviously with painting or sculpture it is much more accessible and of a manageable scale. A formal composition at whatever scale requires that you articulate lines, spaces and volumes so that they relate to one another in ways that you intend as opposed to just making a mess.

Objects or images can be created that are beautiful but have limited or no meaning. Beautiful form was for example clearly understood by the Bauhaus teacher Johannes Itten. Itten revolutionised teaching on form and colour to the extent that his curriculum became the basis of every contemporary art and architecture school’s foundation course across the world. Itten’s beautifully concise books on composition are still on every design student’s essential reading list and provide an insight into how you can determine more scientifically why one line or shape is beautiful and why one is ugly.

As a student I mechanically went through every compositional exercise in Itten’s curriculum as part of one of my elected subjects. Starting with dots, then lines, then shapes, then colours, then forms I completely filled the gallery with drawings. I wasn’t making art, I was exploring the dynamics and lessons of composition. I remember a resident artist coming into the gallery and damning my efforts, saying that I couldn’t become an artist by following a formula. This wasn’t my objective; rather it was to learn to be self-critical so that I could intelligently look at my work and the work of others and understand why it was beautiful or ugly. I wanted to be more than an intuitive amateur who could just recognise attractive forms - I wanted to understand why a drawing or object was succesful.

After my Bauhaus studies I immersed myself in a completely different course called experimental aesthetics, which dealt with a more conceptual approach to art. I made five huge paintings of five different Greek islands which I had visited and the subcultures I had experienced. Looking back I recognise that the paintings were overly figurative and much too busy trying to communicate complex narratives. In attempting to say too much they became visually weak.

I have however continued to paint, although in a much less prescribed way. The marks and forms I make in my paintings now are much more intuitive and, I admit, 100 per cent post-rationalised. I don’t follow a formula, nor do I start with some contrived concept that I am trying to communicate from the outset. What I have found however is that I have developed what I can only describe as a means of making.

I definitely recognise a personal language and a tendency to return to certain shapes and forms I like. The shapes I make either mean something or the meaning emerges as I go. I don’t care what people think of them as the final result is not why I do it. A lot of the time I don’t like the outcome either. It is rather the process of doing it that is much more important to me and what I take from it into architecture.

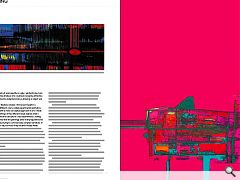

My painting is a larger scale extension of my constant sketch book doodling of structural forms and enclosures; forms that resemble deconstructed ships, bridges and submarines. These shapes combine with grids and imagined landscapes. It’s my personal playground of visual elements that have for me an embedded meaning.

I therefore think of my work in paint as architecturally representative but free from any functional requirement. This freeform play is for me a warm-up exercise like a gymnast free-styling and practising potential moves before a public presentation. A developed visual intelligence and intuitive confidence requires that I continually invest and challenge myself mentally.

I can identify compositional layers I work with that include structural and figurative forms. A structural shape will generally help me compose my painting and allow secondary shapes and characters within the compositions to find their place. The structural shapes represent to me actual structural systems that you might encounter when in a building.

The enclosures or architectural skins that I draw in my paintings I imagine are hung like modern non-load bearing façades. The skins fold around space and are cut and punctuated with holes or, as I see them, urban windows. In my head these skins are representative of a metal rain screen, the hull of a ship, a submarine enclosure or a concrete-clad landscape.

Familiar figures and forms are recycled in my painting process. I remember shapes, storing them away in my head to potentially use in some way in a future design. Using paint as a medium to explore form in this manner is fundamental as it is less easy to control, more fluid meaning you make more mistakes and discover things you don’t expect. It is this lack of control over the fluidity of the paint and the hit and miss marks on the canvas that pose the challenge.

I feel a definite tension between my rational mind and the unpredictability of the paint, the paint sometimes winning by undoing a composition that I have spent considerable time on. When I ‘win’ with a paint layer it means I am satisfied that the relationship of the shapes and colour within the painting somehow works for me.

I also frequently get frustrated that my canvases are too busy, as shapes I have made work in isolation but combined are unsuccessful. To paint over and mask these shapes I have detailed can be painful but the greater gain of the whole canvas working together is the primary objective. Much of the time I remain unsatisfied but I enjoy trying to understand why.

Throwing paint onto the canvas and seeking to post-rationalise the marks I have made did not at first come naturally to me. Architectural education when it focuses on form making tends to promote formulaic and prescriptive methods or more often simple reference to precedent. This approach is no fun, copyist and does not encourage students confident in form making. That’s why I would encourage every architect to try a different approach to form making and to hide their 4H pencil.

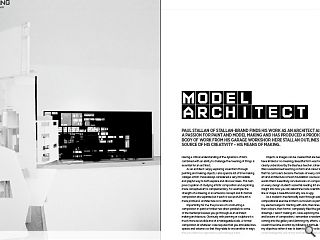

The bricolage models I have been making are an attempt to build three-dimensional representations of my paintings. The models are rough and again not so much about a finished object but an exploration. I enjoy building them up to discover new views. I can for example build a tower shape which when laid flat works better visually. The rules I make and break as I progress.

I take lots of photographs of the models in progress, some of which I incorporate into collage projects. Seeing the models backlit changes them. If I ever get around to showing them somewhere I would have them presented in low light as the gaps, openings and internal forms remind me of how architecture is certainly experienced in Scotland … in the dark.

In summary I am adamant that my exploration in paint, modelling and collage is useful to me as a practicing architect. Having confidence and being clear on how the dynamics of form and colour can benefit design and how meaning can be better realised in architecture in a contemporary way is how it helps me.

With regards to other architects there are many that have practices and pursuits that run parallel to architecture that I imagine inform their work, whether in an aesthetic, musical or literary sense. I have, over the years, taken time to think about the connections between other architects and their art. I previously studied the unseen drawings and paintings of Sir Robert Matthew which his family shared with the office. I was fascinated to make a connection between his artwork and his architecture of the time.

More recently I came across the sculptural projects of Richard Meier. I knew that he enjoyed creating small collage works but his sculpture projects surprised me. The sculptures are cast metal and are very different in their aesthetic considerations as compared with his perfect white architecture.

From Steven Holl and his watercolours (which you can buy from his website) to the computer-generated art of Thom Mayne there is much that can be studied. I know, having experienced working with Frank Gehry, Will Alsop and Miralles, that there are some very direct art/architecture crossovers. Alternatively, Herzog and de Mueron have a different, less direct relationship with art - not having their own art featuring in their work but rather having a more curatorial relationship with artists like Ai Weiwei where ideas are overlaid against a crafted technical architecture.

For me each project is a new challenge and has the potential for new collaborations. Ideas carry through but not to the point where you are simply just making a product. The process of making is for me the best bit of what being an architect is about. The involvement of the client and promoting genuine collaborative working, if managed well, will result in a richer architecture and not necessarily lead to compromise as some think. I supported an arts consultancy practice in parallel to our architecture studio for over ten years, trying to break down more traditional architectural approaches and introduce new processes into the way we work. I did not see the introduction of an artist as a threat to the art in the architecture but rather quite the reverse.

In a recent tribute to Isi Metzstein, Penny Lewis referred to a provocative text Isi wrote that claimed architectural publications favoured ‘operational and social reviews’ of buildings as opposed to ‘architectectonic’ ones. A quote from this text stated; “Essentially, all buildings are parcels of single or closely-packed, multi-cell volumes of varied plan and sectional ordering. The wrapping, with the possibility of local variations in stiffness, thickness, transparency, colour and texture has an intense capability of artistic and functional orchestration, and thus an opportunity for combining artistic self-expression and public pleasure.”

Isi’s description of the syntax of architectural composition is genius, but his assertion that there is an opportunity for self-expression in architecture is something that many architects are deeply uncomfortable about expressing, journalists feel unqualified to review and that the public can deride. Delight in architecture is not folly but an essential requirement of architecture to lift our spirits and celebrate our achievements.

|

|

Read next: Scottish Independence

Read previous: Planning Reform

Back to August 2012

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.