New Town: Hot Date

24 Jan 2018

Edinburgh’s new town is now 250 years old but this passage of time has been marked by nary a whimper from officialdom. In an effort to right that wrong urban design director Leslie Howson sets out a personal ode to this seminal piece of town planning, warning that its very future is at stake should it be sacrificed on the altar of mass tourism. Instead Howson calls for the city to put its people first with a renewed emphasis on placemaking.

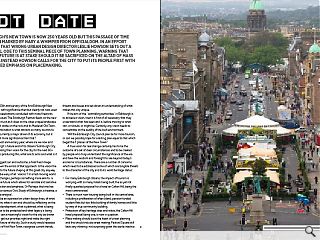

2017 was the 250th anniversary of the first Edinburgh New Town, an event with significance then but clearly not now, even if the new year celebrations concluded with more fireworks and noise than usual. The Edinburgh Festival feeds on the new town legacy as much as it does on the cities unique landscape setting, its great castle on the rock and its Medieval Old Town. This unique combination is what attracts so many tourists to the city and is currently a major driver of its economy, but it surely has much more significance than that?So, in this post anniversary year, where are we now and what of Edinburgh`s future and of its citizens? Edinburgh City Council are devising their vision for the city for the next 50+ years but who is producing this, what are its aims and what is it based on?

A vision suggests an end outcome, a final fixed image. History has shown the errors of that approach. Is the vision the right approach to the future shaping of this great city anyway and should we be wary of all `visions`? In a fast-moving world of growth and changes, perhaps something more akin to `a road map` to the future which allows for sensible and sensitive changes of direction and emphasis. Or Perhaps the time has come for another serious Civic Study of Edinburgh, a treatise; a `comprehensive analysis’.

This would be an appraisal on urban design lines, of what Edinburgh is now, what it can and should be, reflecting on the cities historical development, what is planned, what is being built, what needs to be protected and what legacy is being built. Only then can a meaningful vision for the city be drawn up. We need to get our priorities right and make the right choices for the future of the city. Such a study would reassess the significance of first New Town, recognize current trends, threats and issues and set down an understanding of what makes this city unique.

If the aim of the `controlling authorities` in Edinburgh is to achieve a vision, then it is first of all necessary that they understand what has been and is, before moving to what can, or should, or might be. Certainly, any vision needs to concentrate on the quality of the built environment.

Will the Edinburgh City council plan be for more tourism, or can we possibly hope for a lasting plan equal to that which begat the 7 phases of the New Town?

A true vision for real change certainly has to be the outcome of a set of clear circumstances and to be created by people who truly understand the significance of the era and have the wisdom and foresight to see beyond today’s economic circumstances. There are a number of concerns which need to be addressed some of which are tangible threats to the character of the city and to its world heritage status:

For many Edinburgh citizens, the impact of tourism is worrying with so many hotels being built, the as yet not finally quashed proposal for a hotel on Calton Hill, being the most controversial.

There is much new housing being built in the central area, including a proliferation of often bland, pension funded student flats but too little building of family homes and little by way of true community building.Protection of key heritage sites and vistas, the Calton Hill hotel proposal being one, is now in question.

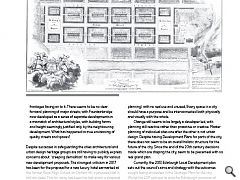

Place making should be at the heart of urban planning and this should include street making. Festival Square still lacks any vibrancy; not surprising given the sterile inactive frontages facing on to it. There seems to be no clear forward planning of major streets; with Fountainbridge now developed as a series of separate developments in a mismatch of architectural styles, with building forms and height seemingly justified only by the neighbouring development. What has happened to true envisioning of quality streets and spaces?

Despite successes in safeguarding the cities architectural and urban design heritage groups are still having to publicly express concerns about `creeping demolition` to make way for various new development proposals. The strongest criticism in 2017 has been for the proposal for a new luxury hotel earmarked at the former Royal High School on Carlton Hill, a proposal that is still not dead. This for many has been the last straw; a proposal seen as `tipping the balance` away from conservation, to inappropriate development.

What concerns those who oppose such drastic developments is not only the insensitive nature of specific proposals are contrary to what most citizens and affected local communities want but that such proposals ride roughshod established conservation planning legislation.

It is the interplay of the buildings and the spaces between, which are and should continue to be the music of the city experience in Edinburgh.To use a term generated by the Architectural Review as far back as the 1960s, we still see too many spaces which are simply SLOAP (spaces left over after planning) with no real use and unused, Every space in a city should have a purpose and be interconnected both physically and visually with the whole.

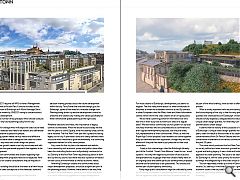

Change still seems to be largely a developer led, with planning still reactive rather than proactive or creative. Master planning of individual sites one after the other is not urban design. Despite having Development Plans for parts of the city, there does not seem to be an overall holistic structure for the future of the city. Since the end of the 20th century decisions made which are shaping the city, seem to be piecemeal with no real grand plan.

Currently, the 2013 Edinburgh Local Development plan sets out the council’s aims and strategy with the outcomes sought being embodied in the Strategic Plan for the city. Whilst the LDP sets out its aims for Edinburgh, provision of quality housing, more jobs, access to services, sustainable transportation infrastructure, maintenance of good air and water quality. The document makes clear that Edinburgh`s economy and encouraging economic development opportunities will be at the heart of the city vision, but is this the only basis for a city vision?

There is an acknowledgment of Edinburgh`s environmental assets, both built and natural and of its World Heritage Site Status. However, the current LDP says only that this may be a material consideration for decisions on planning matters and that ‘many elements of Edinburgh`s built heritage are worthy of protection’, an understatement if ever there was one. NB: UNESCO requires all WHS to have a Management Plan in place with an Action Plan. It should be noted at this time that retention of Edinburgh as A World Heritage Site is currently under review by UNESCO owing to concerns about inappropriate development.

There are a number of key precepts which should surely be at the heart of any future planning policy for this city:

- The drivers for change which will shape the cities future need to be wisely selected and need to be realistic and deliverable as well as sensitive to place and people.

- The Planning system needs be truly robust and effective in order to be better able to safeguard the cities rich urban heritage, its key vistas and urban design set pieces.

- Further urban growth needs to be fully structured and with a more holistic less piecemeal approach than appears to be the case at present.

- Concerns from communities and citizens regarding high impact development proposals need to be respected. New mechanisms for citizens consultations may be required in future.

- Community building should be at the heart of all new house building with clear concepts as to the character, scale and facilities.

- Urban design skills must be brought to bear into the decision-making process about the future development within the city. Terry Farrell the one-time design guru for Edinburgh, spoke of the need for a mindset change from Planning being driven by reactive development control to proactive and creative city making and called specifically for three-dimensional spatial planning at the right scale.

Whatever decisions are made, the importance of legacy cannot be overstated. What we decide to build today we live with for years to come. Equally, what we destroy today cannot be re instated. The first New Town plan left a great and lasting legacy to this city. It provided a bold and clearly defined urban structure which was able to grow incrementally, in a continuing organized manner for all its seven phases.

Any vision for the city has to be relevant and realistic. Land ownership and economic power and politics have often been the controlling factors and will probably continue to be so. Delivery of the first New Town required acquisition of farm land by the city council but there was also a political will based on both social, environmental as well as economic needs.

Informing Edinburgh citizens and communities about major development proposals, should be a significant part of the planning process. However, there seems to be very little by way of early consultation, probably one reason why there is so much community opposition to major developments. For most citizens of Edinburgh, development just seems to happen. The first many know about it is when announced in the press or when the bulldozers arrive on a site. By contrast, in other European cities like Milan, there are Urban Information centres which inform the cities citizens on an on-going basis.

We do have a planning portal for information but who has time in their busy lives to trawl such sites on a regular basis? We also have a community council system run by local voluntary worthies who are consulted and do comment and even oppose development proposals, but they are rarely fully representative of their communities. When, as with the Royal High School proposal, local residents do come together they can demonstrate their opposition, though they are only effective if they are then able to put pressure on their local councillors.

Surely in this internet age, cities like Edinburgh (already part of the Scottish `Smart Cities Alliance`) need to use `smart systems` not only with regards to provision of services and transportation but to gauge what their citizens really want on an ongoing basis and before particular development proposals become too far advanced to be questioned. This should be a normal part of participatory democracy.

Early stage public consultation might be criticized by some as off putting to investors in new development within the city, but the opposite is likely to be the case, as citizens views will be part of the initial briefing, more so than is often the case at present.

What is surely important with any envisioning process for the future shaping of this city, is that the very special urban qualities and characteristics of Edinburgh`s historic centre should be fully respected, safeguarded and valued for their unique urban design qualities, for what they can inform city planners about urban design.

It seems that the history of the successes of conserving of Edinburgh`s unique urban design qualities has over the years, been the result of the activities of its citizens and conservationists from Sir Patrick Geddes and the New Town conservation movement to the various community groups of the past 20 years.

The vision which produced the first New Town, was based on social, political and even economic grounds and produced a great and lasting legacy. It was a bold and holistic and wise approach to urban planning. The issue to be debated now for Edinburgh is, will the cities priority for economic growth outweigh the safeguarding of the cities unique built heritage?

Tourism reportedly makes up a third of Edinburgh`s income. So, bearing in mind that Edinburgh`s greatest economic asset is the city itself, to destroy or even erode that asset will significantly erode an important part of the city’s economy.

|

|

Read next: Housing Crisis: The New Normal

Read previous: Hawkhead Centre: Looking Good

Back to January 2018

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.