Gray Dunn: Factory Floored

20 Oct 2017

Gray Dunn Biscuit Factory has long stood as a Kinning Park landmark, known to thousands of motorists speeding past on the nearby motorway. Despite enjoying a brief twilight spell as a crucible for graffiti and street art it is now no more, Mark Chalmers sees if any crumbs of comfort can be drawn from its demise.

There is a German word, sehnsucht, which has no direct translation; roughly speaking it means an inconsolable longing for something. The Russians have toska, which is a great anguish without any obvious cause, while the Portuguese coined saudade, a mournful feeling of nostalgia for something you’ve loved and lost. Those evocative words don’t translate into Scots, but the feelings are familiar. Is it possible to feel sentimental about a biscuit? Or perhaps even a biscuit factory? Most of us ate Blue Riband chocolate wafers when we were in short breeks, so they counted as a Scottish tradition. Not any more. The company behind them, Gray Dunn, went out of business in 2001. Their biscuit factory in Kinning Park lay derelict for many years, a giant brick bookend standing against the motorway. It was finally demolished in July, but we still feel pangs as we drive along the M8. “In 1853, a Quaker set out from his farmhouse home in the North of Scotland to seek fame and fortune in the City of Glasgow. And so it was that John Gray, in partnership with Peter Dunn, a local flour miller, commenced the manufacture of biscuits, bread and cakes and thus laid the foundation of Gray, Dunn and Company Limited.” Within a year, John Gray had fallen victim to cholera, but his brother returned from London to run the business. Under William Gray’s management, the firm outgrew its original home in Morrison Street within a few years and moved to a brand new factory on the Southside, in Kinning Park.Kinning Park was conceived in the 1830’s as a model village, but thirty years later it had become arguably the first industrial estate in Europe. Lying outwith Glasgow proper, for a time Kinning Park was Scotland’s smallest independent burgh. It grew rapidly from the 1860’s and was served by Mavisbank Quay, a dedicated railway branch and later by two subway stations. By the 1880’s, the streets were lined with factories and warehouses, including a boiler works, wire-weaving factory, rivet manufacturer, confectionery works, flour mills, grain stores, copper smelter, and sailmaking factory plus several engine works, ironfounders and colour works. Plus, of course, Gray Dunn’s bakehouse which opened at the northern end of Stanley Street in 1862. In January 1875, the original bakery was destroyed by fire. Its replacement, designed by John Baird junior, was the first of many reconstructions and rebuildings. It’s that process which made Gray Dunn noteworthy, creating a long line of extensions that show how industrial architecture would evolve over the course of the next century.

Like other Quaker confectioners such as the Cadburys and the Rowntrees, the Gray family inter-married within the movement, and in 1893, architects Stark & Rowntree designed two large extensions at 115 Stanley Street. It just so happens that Rowntree (a scion of the chocolate family) had married Mary Anna Gray, daughter of William Gray… By the turn of the century, the firm was caught up in fighting a Battle of the Biscuits: its great rivals were MacFarlane Lang, another Glasgow firm whose name has disappeared in recent years. Elsewhere in the city, Bilsland Brothers ran the Hydepark Bakery: the Bilslands became partners in Gray Dunn in 1890, then Gray Dunn’s in-laws at Rowntrees of York bought a stake in the company in 1924. By now, the bakery ranged from load-bearing brickwork in the 1870’s block on Milnpark Street, through the fireproof cast iron-framed 1890’s extensions designed by Stark & Rowntree, to the Hennebique-style octagonal concrete columns in the south block of 1934, and finally a concrete-framed block from the 1958, with spandrels of red Darngavel brick, forming the courtyard which faced the M8 motorway. The 20th century extensions were designed by Watson, Salmond & Gray, and having reached its final form, Gray Dunn’s Kinning Park bakery employed around 1200 people. The firm produced Breakaways, chocolate digestives, Hampden Caramel Wafers, Duet biscuits and chocolate gingers: but its best seller was the Blue Riband, and business was so good in the 1950’s that Gray Dunn opened a second bakery, on Hillington Industrial Estate. By then, the manufacturing process was mechanised.

Biscuits were baked in conveyor ovens, 70 metres long, then enrobing machines coated them in chocolate. The production line was extended when wrapping machines were developed by the Baker Perkins company: the very first examples of their “Flowpak” machine went to Gray Dunn in the late 1950’s, for the Blue Riband wafer. The bakery was arranged vertically, layer upon layer, just like a Blue Riband. Raw ingredients were taken to the top of the building. The Mixing Department was on the fourth floor. Biscuit Manufacturing including the ovens, biscuit cutting and packing were on the third floor. Tin Washing and chocolate packing departments lay on the second floor, and warehouses sat on the ground floor. Today, modern industrial bakeries such as Burton’s Biscuits at Sighthill in Edinburgh are laid out on one level, and the production line snakes around a giant shed. The process is made to fit the building, rather than vice versa.

Alongside progress inside Gray Dunn, came the re-making of the city outside. The film-maker May Miles Thomas was brought up nearby in the 1960’s. “Glasgow is where I was born and raised. Sadly all of the places I lived, studied and worked in have been demolished or altered beyond recognition. Never has a city shape-shifted more.” Much of Kinning Park was lost in building the elevated section of the M8 south of the Kingston Bridge, but Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Scotland Street School was saved, along with Gray Dunn’s bakery. The route of the motorway deflected to avoid them. However, Stanley Street was severed and tenements around the bakery were pulled down, leaving its southern gables exposed to sixteen lanes of traffic. “How easily the past can be erased.

Growing up in Kinning Park in the mid-1960s it was normal for entire streets to disappear in the space of days, so I have no illusions about the permanence of things. During my formative years, it was usual to see torn gables, split into variations of wallpapers, often with their fireplaces intact, clinging on, gravity-defying.” Rowntree Mackintosh became part of Nestlé in 1988, but Gray Dunn was sold to Hill Biscuits in 1992 then bought out by its managers in 1997. It was independent again, for the first time in eight decades, but struggling to recover from another disastrous fire which had destroyed its wafer production line. The firm didn’t skimp when it came to repairing the damage: “Our wafer ovens are the fastest and most efficient anywhere in the world, installed as recently as 1996, and our wrapping machines have the capability of very high speeds to keep up with the growing demand for our quality biscuits.” The production line could produce 2,000 Blue Ribands a minute. Nestlé hung onto the Breakaway and Blue Riband trademarks after selling the company, so Gray Dunn mainly produced own-brand biscuits for supermarkets. At the turn of the 21st century, the firm employed around 250, but in January 2001 it went into receivership, after losing a major customer.

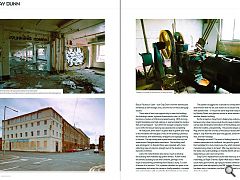

May Miles Thomas recalled Gray Dunn from her childhood in Kinning Park, then returned decades later when she directed the film “Solid Air”. In 2002, her production team took over the top floor of the empty bakery, and while exploring the building she found some beautiful original artwork for biscuit wrappers, lying abandoned in a drawer. She later revisited Kinning Park for her film and accompanying website, The Devil’s Plantation, tracing a series of psycho-geographic journeys across Glasgow. The film searches for connections between places which don’t make it into conventional histories of the city – from prehistoric sites on the outskirts, to locations just like the ghost streets of Kinning Park which disappeared under the motorway. Temporary uses, such as renting space out for film production, events or storage help to fill a gap, but a transformative idea is often needed to secure a building’s future. The potential was there to create something along the lines of the Custard Factory in Birmingham, or indeed the Biscuit Factory in Leith – but Gray Dunn’s former warehouses remained as self-storage units, and the rest of the building lay vacant. There was at least one opportunity to save the building: the building’s owner, Ivyhouse Investments, sold it in 2008 to become a mixture of offices and warehousing. With its long, bright floorplates and high ceilings, it seemed ideal for studios, flats and workspace – but when the storage company moved out in 2011, the biscuit factory was abandoned completely. At that point, there wasn’t a great deal of graffiti and many of the windows still had glass.

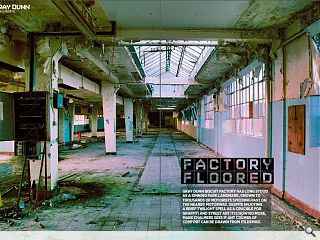

Hints of the building’s previous life remained, with letterheads, wrappers and signage lurking in corners. The top storey was a penthouse over the city: the views across Glasgow were panoramic. The building itself was photogenic: its flooded floor was carpeted with moss, reflecting rows of columns straight out of the derelict car factories in Detroit. Later, the metal thieves who did so much to destroy the building were followed by graffiti writers. A few visited the derelict building to see their artwork, perhaps in the hope of discovering something from Balzac’s story, “Le chef d’oeuvre d’un inconnu”. In it, a painter devotes ten years to his masterpiece but when the canvas is finally revealed, it consists of a swirl of colour with a perfectly-formed foot at one corner.

The painter struggled for a decade to convey feeling and emotion with his art. but visitors to his studio only saw a well-painted foot – in much the same way that many drove by Stanley Street and glanced across at what seemed like just another derelict building. So the artwork in Gray Dunn’s bakery lay undiscovered, because only a few curious souls found a way in before the canvas was destroyed. Demolition of the buildings started in 2013, then halted, unexpectedly.

The process began again this May, and the last few crumbs of the biscuit factory were cleared away in July. Now we drive past the gap site, sense what once was, and feel nostalgic. Nostalgic for what? The scent of baking biscuits, like a warm reassurance of childhood, has gone for good. We feel nostalgia for a truly mixed-use city, which retained manufacturing close to its heart. We may also feel regret that the bold, city-scale buildings on Stanley Street will soon be replaced by a cash-and-carry shed. Gray Dunn’s replacement could have faced up to the motorway, as Ralph Erskine’s Byker Wall does in Newcastle. It could have gone further, by trying to restore a little of the urban grain which was disrupted by the M8. Instead, Kinning Park has been lost in translation, and that’s guaranteed to bring on a dose of saudade.

|

|

Read next: St Cecilia's Hall: Noteworthy

Read previous: Dunfermline: Word on the Street

Back to October 2017

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.