Glasgow School of Art: Mack 2.0

11 Jan 2017

When fire ripped through the priceless innards of Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s sublime Glasgow School of Art many feared the worst. But the irony is that in losing one of the city’s most treasured interiors we now know more about its history and creation than ever before. We look at the latest revelations.

When fire ripped through the priceless innards of Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s sublime Glasgow School of Art many feared the worst but the irony is that in losing one of the city’s most treasured interiors we now know more about its creation and history than ever before.This is down to the forensic work of a team of conservation experts led by Page/Park architects who have over the subsequent months painstakingly raked through the ashes of the old to learn how best to build anew. It is an inclusive and measured approach necessitated by a project fraught with passions and sensitivities on all sides including those who think the restoration should not be attempted at all.

Speaking at a Friends of the GSA meeting Liz Davidson, senior project manager for the Mackintosh project, said: “We get asked a lot if it was the Mona Lisa you wouldn’t be restoring it. Well, no we wouldn’t but Mackintosh didn’t physically build the school. He designed it and others built it for him.” In making this argument Davidson reaches out to the distinction between autographic and allographic art, a distinction traditionally made to separate forgeable from non-forgeable art which comes into play here when discussing the ‘forgery’ of Mackintosh’s work. Whilst in painting an artist will directly construct their work in paint a playwright will see their work performed by others. Davidson points out that architecture falls between the two disciplines with someone else building the designs - but in a process that usually takes place just once.

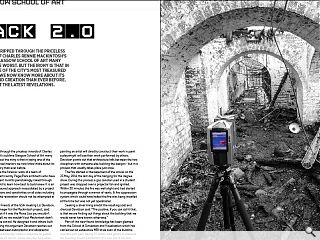

The fire started in the basement of the school on the 23 May, 2014, the last day of the hanging for the degree show. During this process a gas canister used in a student project was dropped over a projector fan and ignited. Within 30 minutes the fire was well alight and had started to propagate through a warren of vents. A fire suppression system which could have halted the fire was being installed at the time but was not yet operational.

Seeking a silver lining amidst the resulting soot and charcoal Davidson said: “The positive, if you can call it that, is that we are finding out things about the building that we would never have known otherwise.”

Part of this new-found knowledge has been gleaned from the School of Simulation and Visualisation which has carried out an exhaustive MRI-style scan of the building over the past year, taking 20 billion data points to measure the building down to millionths of a mm. But it has also been a process of good old fashioned detective work with the team scanning archive photos, testimony for clues whilst archeology has built an incredibly detailed understanding of how Mackintosh’s builders delivered the design by cataloguing and studying surviving debris.

Davidson said: “Mackintosh did, thankfully, build a structurally robust building. Many thought the school was lost and would simply collapse but it didn’t. He built an extraordinarily strong, muscular building with brick lined walls that have held up remarkably well. We can walk through pretty much every part of the floor. We lost the books, the paintings and the wonderful library itself but the space is still there.”

Alighting on Page/Park to conduct the work having dismissed a who’s who of international architecture (and one team from Turkey who offered to set-up a local office in Manchester), Davidson’s first objective is to ensure the integrity of any replacement. “As a client, you need to know that the building will be safe, future proof and functional for use of students”, Davidson said. “They are doing a miraculous conservation job and also installing Wi-Fi connectivity and disabled access.”

Period photography of the school from 1909 is being scrutinised in minute detail for clues as to the building’s original appearance, throwing up many surprises along the way.

Indeed, the School of Art calculates that whilst it has lost four per cent of the building and 17 per cent has been damaged the bulk of the building has been left either utterly untouched or with only minor water and smoke damage. In practice this means that the refurbishment will require relatively unobtrusive work such as re-skimming plaster and relaying timber floors.

Elsewhere the work will be more involved, particularly the reinstatement of the famous library lanterns. “Most are in bits”, lamented Davidson. “But we’re pretty certain we’ll be able to restore all of them. They will not be black but antique brass they were originally before they were painted due to tarnising.” More prosaically issues such as the harling to the back of the building, which wasn’t looking its best even before the fire, will be redone using Portland cement.

Articulating the dilemma facing conservators at every stage in terms of what to restore and how Davidson added: “Whilst we would never ever have wished for the loss of the library one thing we can say about the space is that we’d already lost the public use of it for many years, it could only be accessed by appointment. It was the one room which had become precious. If we restore it, it will become a room like any other and we can use it as a library again 24/7.

“We don’t know what Mackintosh would have done but If Mackintosh had built the library, walked out and it had burned down in 1909 he would have just said here’s the drawings, do it again. If he had continued to live and evolve as an architect then he wouldn’t have built it again, he would have changed.” Comparing the predicament to a DAB radio Davidson declared: “… we’re building something which looks the same but performs better.”

Outlining some of the biggest discoveries thus far David Page, head of architecture at Page\Park, said: “This project is painful, not just because of the story behind it but the intellectual challenges it presents. There are no clear answers. It is constantly provoking us.”

Wielding a pointy stick with a rusty nail still embedded on the end Page looked to be venting these frustrations on his audience but then said: “It was nailed together. It wasn’t tongue and grooves, or screws. It was nailed together!

“We’ve measured every inch of the school. We have 20bn data points but they don’t look inside all the surfaces. Our guys had to spend months measuring the inside of everything. Our approach is millions of little steps, there is no grand conception, towards a reconstruction and restoration. Our starting point is an absolute admiration for what Mackintosh achieved but it’s complicated by what’s been left there. When it was completed in around 1910 it was recorded in photographs and that’s the closest approximation of how Mackintosh left it. So we’ve taken a stance that 1910 is roughly the period to return to but it is adjusted by an understanding of what happened in the first phase of 1897.

“Sometimes things done in the first phase were redone, it’s not as simple and straightforward as two halves. Post 1910 there were adjustments carried out until 1913 by Mackintosh and post 1913 through to the present day. There were lots and lots of adjustments like fire doors and new windows. It’s further complicated by the need for a fire suppression system and smoke detectors. There’s going to be an infinite number of conversations to come to the best approximation of a position.”

In short what the conservation team are seeking isn’t a carbon copy of an uncertain past but to reclaim the ‘mantle of creativity’ and broader themes of ‘repetition, grids and transparency’ which define the art school. Page added: “Page has created this amazing encyclopedia which we see as a crucial part of the reconstruction, not simply the artefacts. Our methodology is piece by piece, mm by mm, nail by nail, to reconstruct a room and ultimately the school. What informs that process is this cycle of thinking. We can identify Mackintosh’s decisions and the origin of our decisions so others can retrace those steps.

One of the defining elements of the school, its vertical windows, were installed in 1947. Page explained: “Keppie was gone then so it was possibly Henderson. He tried to improve the Mackintosh building but that’s the iconic image of the Mac which everyone has in their minds. This is what we all grew up with and drew in our sketch books but it wasn’t what Mackintosh intended. The problem was the windows leaked and so they were strengthened, with thickened frames and changed orientation.

“I’m flexible. If the consensus view had been to restore to the 1947 detail for all the windows, I could have gone with that. If we decided, we were going to replace all the windows (including those that weren’t damaged) with the original design I could go with that too. If we were going to restore the windows in the library to 1910 and keep the rest of the windows, I’d be against that – I struggle with the inconsistency.”

In this case the decision was taken to revert to the horizontal look Mackintosh envisaged but as Page points out: “We know those windows leaked!

“We’ve found the original window sketches to have them rebuilt but are faced with the task of ensuring they don’t fail a second-time round. We think the original windows were constructed in pieces whereas our engineers think they can construct this as a giant lattice to give it rigidity and preventing movement pulling the putty loose. We can conceive of it as one piece. So not true to the original but adjusted.

“Another example is the detail of the library. In 1909 the librarian said he wanted a window so Mackintosh moved the office. I think that would have been painful for him because it broke the symmetry, there’s a judgement to be made. There’s no straight forward answer but whatever we do we will have recorded the journey to get there.”

A crucial key detail lies in the upper floor ‘hen run’ where it was found that the pitch of the glazing had been increased at some point, probably before 1950, to eliminate leaks caused by pooling water. Page stated: “We can do what Mackintosh dreamt of. We can adjust that level back. In the 21st century surely it needs to be double glazed but should we? I could have gone with it but the fury of my colleagues came upon me. On this side it works well because if you double glaze this it cooks in summer. On the north side, we’ll put more heating in.”

One of the key differences is in the use of colour with the school being far removed from the white walled spaces we are familiar with today. Period photos prove that the hen run was originally dark before being painted white and much of the interior, which was cheap Douglas Fir, was painted a beautiful green. Moveable partitions were also discovered in the studio spaces which weren’t known of before. Page observed: “We think that the timber was stained with oil paint to mask all the variations in the timber. The discoveries that we have made in the process of this journey add to the immensity of Mackintosh’s creativity.”

The 23 May 2014 may have been a dark day for the Glasgow School of Art but the weeks and months since have informed our understanding of Mackintosh to such an extent that we can now begin to reappraise Mackintosh’s masterpiece in a new light. Armed with this knowledge the school’s future now looks brighter than it has eve3r done before.

|

|

Read next: Urban Realm TOP100 Architects 2017

Read previous: Oriam: Pitch Perfect

Back to January 2017

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.