Charettes

13 Jan 2016

Public engagement is in vogue with the Scottish government commissioning a series of charettes designed to empower those who have become disenfranchised. But is it ever really possible to speak with one voice when everyone is talking? Urban Realm sat down with three exponents of the process to hear what they had to say.

Ever since Andres Duany first parachuted into Scotland to kick-off the charrettes programme back in 2010 church hall’s up and down the country have been a hot bed of map defacing, passion, and argument as a series of government backed week-long intensive design sessions roll from town to town, with Montrose, Arbroath and Greenock next on the hit list. But with cynicism rife amongst the locals, not to mention concern amongst some architects at the short-term nature of the process, are they more than mere talking shops? To find out Urban Realm sat in on a round table discussion with three consultants who have led the most recent charrette to have been published, Elgin.The gap between profession and public is rarely starker than in architecture and the need to engage with community groups is clear, but how? Does conversation with those on the ground, skirting client and developers, ensure that designers are more emotionally involved and so have a greater personal interest in seeing things improve?

Douglas Wheeler of Douglas Wheeler Associates, said: “The Scottish government first got involved back with Andres Duany in 2010 with a series of charrettes in Dumfries, Grandholm and Lochgelly. In some ways that established a benchmark but the budgets involved then were really quite significant.”

Graham Ross, urban design specialist at Austin-Smith:Lord, continued: “The simple fact was that we and our peers were doing a lot of stakeholder engagements in different shapes and forms using different techniques. So while the charrette process is something the Scottish government has promoted over the last four years the constituent techniques are a concentrated form of community engagement which already existed.”

Peter McCaughey, lead artist at Waveparticle, added: “The concept of the charrette is a little like PechaKucha, it’s a system for succinct, intense communication within groups and bodies. You can frame it quite easily and it sounds fancy. At its best a charrette has a sense of incredible intensity about it and that’s what energises and galvanises, even when people are worn out and have been consulted to death they’ll still turn out to these things because they are very dynamic. Part of the principle is you come into a room and things are actively being designed in front of you, you can see your idea being turned into a drawing or piece of analysis or into some other form. “

The charrette process is more than a simple rebranding of pre-existing techniques however, with the primary added ingredient being immediacy, telescoping down to three or five days what might have previously taken years. In today’s world we want it all. Now. Ross observed: “The charrette brings the power to convene and bring people together who wouldn’t otherwise necessarily do so it’s an interactive/iterative process that allows people to inform and directly influence and engage. You could do that over a longer period of time but sometimes the time limitation really helps.”

Another difference is the active solicitation of professionals from beyond the built environment sector, as McCaughey explains: “We always feel privileged to come in as a public arts organisation. We don’t come into talk about public art. We bring a set of ideas from a slightly different creative field into the heart of the team. That allows us to inflect everything with an emphasis on creative approach. I was educated under the principal that context is half the work so you can export ideas which worked in different places to an extent but you are always trying to make the most of the bespoke nature of the opportunity and the place. If the budget could afford it we would have peace and reconciliation experts, anthropologists and poets on the team. “

Part of this work involves breaking down walls that have traditionally silenced the shy, disaffected and cynical, as Ross mused: “It’s not quite guerrilla tactics but it is about going out to the pubs, clubs, shops and bus stops to promote discussion and set the agenda before the charrette commences. The other thing is that within the team there might be some who are very familiar with a place and others who have never been there. We really make that a benefit rather than folk coming in with preconceived ideas.

“What Peter and colleagues are adept at doing is identifying key individuals within the community whether business people, residents or third sector individuals who can come forward and act as ambassadors for the process and give us direct access to local knowledge.”

McCaughey continued: “We will always print a map of a place as large as we can. You can put it anywhere and people cannot help but gravitate to it, but as they stand on it they are about 500m up from where we print it. It privileges people with an overview that is normally restricted to the professional. It’s a brilliant way to draw out knowledge, perception and subjective interpretation. We don’t go in with a questionnaire, the question that you ask informs the answer that you will get. It’s bogus to attempt to be neutral in those situations, so we go in as our curious selves, with an interest in culture, history and the people we meet. We’ll ask people to identify where they live or somewhere they have an association with. We ask them to mark somewhere that needs to be improved with a red dot.

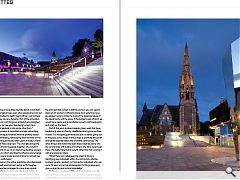

“You cannot completely synopsise the history of a place in a charrette and analyse everything that ever happened. At the very start you’re also acting on your intuition. In the case of Elgin a walk down the Main Street tells you so much. “

A chief driver of community interaction is the relative affluence of the population, with Elgin driving more active participation than down at heal Johnston where apathy was order of the day. McCaughey ventured: “We have worked in quite a lot of poorer places across Scotland and one of the poverties you come across is poverty of aspiration. If you are unlikely to think your opinion is worth anything or will change anything you are unlikely to contribute. Therefore one of the principle challenges is to encourage people to believe that the knowledge they hold is valuable. If you get the children involved then the parents come out, six to nine year olds have amazing knowledge and fantastic aspirations. It shames all of us and really accelerates the process.”

Citing an example of specific influence Ross recalls a charrette at Brechin which was usurped by 20 interlopers on their BMX’s and skateboards. Ross recalled: “It was quite clear they had an agenda they wanted to discuss and sure enough it was about developing a skate park in the soon to be vacated leisure centre. We then facilitated a charrette looking at that particular topic to allow them to take that on.”

Turning to the post-charette space McCaughey observed: “It’s so essential that a charrette doesn’t end up as a 150 page image report that sits on a council shelf. The danger is that you whip up such a fervour in a place, some of the rooms we’ve booked have been crackling with energy. You really don’t want to see that dissipate but rather within a six month period say look, we’ve done these things.”

So does the charrette process ever really end? Ross said: “The never-ending charrette, it’s like Bob Dylan’s tour. There should be a method to identify an after-care process for the charrette where nine months later we do a post charrette review of what’s working and what’s not and try and help to unpick any blockages. If there was a pot of £30-35k for the charrette but also the same again to ensure that some of the activity could definitely be delivered.

“When we first got a place on the Scottish sustainable communities charrettes framework there was a degree of scepticism from our team about the benefit of the process. It’s good to have a healthy scepticism of the process to address some of those potential shortcomings. It’s not the only show in town and there are other ways of doing part of the charrettes process.”

McCaughey added: “We know there’s a type of daftness associated with the 30 year master plan. We assume this is the intelligent way to do it. It’s so complex trying to analyse the present in relation to the past or trying to analyse the future. One of the things that emerged was the possibility for lots of short term changes, a type of prototyping process such as in Helensburgh where we re-routed traffic for a month.”

Ross concluded: “We’ve been very struck by that community first approach in Scotland which is unique in the UK. There is a good body of work going in here, There are bound to be occasions where expectations have been raised too high or promises haven’t been kept there is pragmatism as well as a vision. From day one the first thing we did was have a cost consultant on board.”

Looking to the future McCaughey has an eye on exporting hard won expertise as the home market matures: “We’ve grown the tools we use together through a process of trial and error and we’re keen to share them. There has been an extraordinary level of knowledge gained over the past 2.5 years.” Referring to a recent speech made by Alex Neil (cabinet secretary for social justice, communities and pensioner’s rights) given at the SURF Awards McCaughey warned: “He really gave a no holds barred account of the cuts that are coming that are really going to hit infrastructure, communities, social housing.”

Charettes come across as a slightly pretentious addition to the urban design lexicon but the need to offer immediacy in a world of near geological change, where masterplans are measured in decades has never been greater. In an age of social media and instant gratification there is a need to engage with the public in real-time, the need to engage in real-time. In this Scotland is well placed to take the lead.

|

|

Read next: Ballantine Bo’ness

Read previous: University of Glasgow

Back to January 2016

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.