Cold War

15 Jan 2015

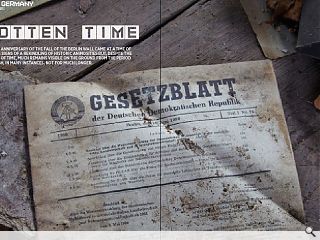

The 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall came at a time of ominous signs of a rekindling of historic animosities but, despite the passage of time, much remains visible on the ground from the period although, in many instances, not for much longer.

We arrived in the former Eastern Germany to explore the proposition that, 25 years after the Wall came down, reunification has led to the complete absorption of the East by the West. The German Democratic Republic or DDR dissolved overnight, it seemed, and soon there was only one Germany. Today, whatever remains of the East is found in a diminishing number of places which lie in the countryside beyond Berlin: discovering them means travelling beyond the usual scope of architecture journalism.

Berlin itself is an anomaly. It is untypical of reunified Germany, far less the DDR which went before. It’s a world city, yet Berlin property is surprisingly cheap. It was a divided city, but now it appears seamless. Today only a fragment of Wall remains, and Checkpoint Charlie is a mere photo opportunity for tourists. The Kreuzberg has become a bohemian area full of hipsters, and the modern day Ku-Damm retains little of Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin.

So we travelled out to the towns of Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Brandenburg. Dresden has been beautifully recast as a cultural centre, although the inner city is ringed with dereliction. Leipzig has new high-tech car factories, but a few years ago the Shrinking Cities project discovered that of 320,000 flats here, 55,000 lie unoccupied. Chemnitz, Magdeburg and Zwickau have suffered in similar ways.

The chill and austerity which followed the partition of Germany in 1945 led to a mass emigration from the East. Before the Wall was erected, around 20% of East Germans fled westwards. A similar exodus followed its destruction. Dessau lost 10% of its population in the decade after reunification and by the year 2000, unemployment was running at 30%. Halle lost 70,000 inhabitants in the same period, and Leipzig lost 100,000. By the start of the 21st century, both had an unemployment rate of well over 20%.

Either side of the millennium, the former East German cities dealt with the symptoms of emigration by demolishing thousands of vacant buildings. Their efforts to support tumbling property prices erased much of the former East Germany. Today there are few overt memorials to the DDR in and around Saxony-Anhalt, but the past hasn’t been completely forgotten.

Instead, it found expression in Ostalgie, a German term for nostalgia about the good old days of the DDR. Folk in the East still compare the secure way of life in a socialist country with the chaos of reintegration. Leipzig, Magdeburg and Premnitz are still very much works in progress. Their former backdrop – murals of Lenin, endless blocks of Systembau housing, the coughing Trabant cars and rattling Tatra trams – seem to sum up life in the Eastern Bloc.

On the other side of the Wall was a different Germany. The Bauhaus influence extended from Mies van der Rohe’s architecture and the Vorsprung durch Technic approach to car design, to Dieter Rams’ consumer goods for Braun and Jil Sander’s fashion. A sophisticated yet austere functionalism seemed to characterise West Germany, whereas in the East there was just austerity. Yet for the duration of the Cold War, the Bauhaus at Dessau lay deep in Eastern Germany.

In many respects, the division between the Germanies was artificial and after 1989 politicians were keen to sweep it away. So where would you search for authenticity, 25 years after the Wall fell? Where to reveal the mechanisms at work? What has prompted the redevelopment of some sites, and the demolition of others? As James Meek would have it, these are events “that are too fresh for history, too old for journalism”.

There is one obvious starting point. Beelitz-Heilstätten is a derelict sanatorium as large as a town which lies in dense forest beyond the outskirts of Berlin. It was commissioned at the end of the 19th century by the German national insurance fund to cope with an epidemic of tuberculosis. The site spreads over 200 hectares, with a TB sanatorium north of its own railway station and a convalescent hospital to the south, plus its own farm, bakery, butchery, laundry, nursery and power plant.

The first phase of Beelitz was designed by Heino Schmeiden and Julius Boethke and built between 1898 and 1902. Development at Beelitz parallels Germany’s history: built using the wealth of Imperial Germany, almost brought down by the bankruptcy of the Weimar Republic, the rise of the Nazis led to it becoming a wartime infirmary, and behind the Iron Curtain it became the largest military hospital outside the USSR.

The sanatorium’s modern history began with the fall of the Berlin Wall, which signalled the end for communist East Germany. In December 1990, the GDR’s former president Erich Honecker was admitted to Beelitz after being forced to resign as head of state; in 1994 the Soviets finally gave up the hospital. SInce then, Beelitz has mostly lain abandoned.

Beelitz is effortlessly photogenic. Its materials are lavish, the detailing is ornate and the Beaux-Arts buildings have a fading grandeur. The communists left their mark, from motivational murals which peel in the sports hall, to Cyrillic names stencilled on doors and the copies of Pravda used to wallpaper some rooms.

Yet the experience of walking its long-abandoned corridors is both fascinating and disconcerting. You experience a sort of enhanced reality, because every glance is overlain by images you’ve already witnessed. For example, you feel slightly cheated when you turn a corner in the Bathhouse and see a view straight from the video for Rammstein’s Mein Herz Brennt. Beelitz is no longer part of the DDR; it has taken on a life of its own.

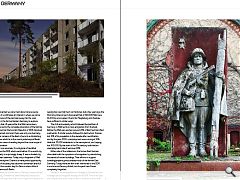

Instead, you yearn for an authentic Eastern Bloc experience. Maybe you could try Fliegerhorst Zerbst, which was one of the first airfields in the world to operate jet fighters. The Luftwaffe launched Messerschmidt 262’s from here against Allied bombers during the last-ditch effort of April 1945; a few weeks later, the Nazis left and the Communists arrived. The 126th Fighter Aviation Division operated MiGs from Zerbst between 1951 and 1992: its Plattenbau blocks, built using large-panel precast concrete systems in the 1960’s, once housed the Red Army.

Zerbst was abandoned in 1992, and most of the western side of the airfield is now covered by a solar farm’s photovoltaic panels. The final traces of its past are being cleared to make way for further development, and even the overgrown sculptures are being crushed for hardcore. Today it requires a powerful imagination to evoke what the airfield once was – a bulwark to ensure the safety of the Rodina, or great Russian homeland – and to envision what it might become.

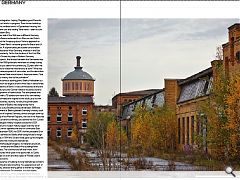

Perhaps the DDR’s spirit lives on at the former railway works in Magdeburg-Salbke, despite the fact it has been destroyed twice in the past 70 years. The main car repair shop was built in the late 1800’s and is enormous: it measures three hectares in area. At the outset of World War 2, Hitler believed that Berlin was impregnable and that the cities to the east were immune from enemy bombing; by the autumn of 1943 he discovered that nowhere was beyond the reach of the RAF.

On the night of 21st January 1944, Bomber Command targeted Magdeburg for the first time: a few hours later, the city centre was a wasteland and over 80% of the railway works had been destroyed. After the war ended, RAW Magdeburg railway works was rebuilt to carry out wagon repairs: it also made hammers, wooden fences and ploughshares. Until 1990, it even produced drive shafts for the Trabant.

After reunification the works became part of Deutsche Bahn. From 1200 employees in 1992, it shrank to nothing by the end of 1998 after which it was stripped clean by vandals and thieves. It took several hours for us to walk around the ruined halls of the former DB Werke Magdeburg, and what we discovered captures the devastation of the German railways caused by reunification. The railway works is Longfellow’s Wreck of the Hesperus on dry land.

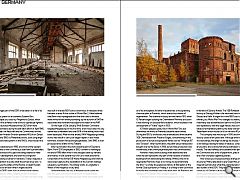

Understandably, the city of Magdeburg has spent the past few years working on schemes for its regeneration; unfortunately, they will wipe out much of the site’s history and all of its atmosphere. Another industrial relic is the sprawling chemical plant at Premnitz, which stands less chance of regeneration. The chemical industry arrived here in 1915, when IG Farben began building the Chemiewerk Premnitz and soon it was working on cellulose fibre research, which resulted in the development of “Vistra” rayon in 1920.

IG Farben played a grisly rôle in World War Two, but afterwards the works at Premnitz became state-owned. During the 1950’s, the factory was extended and then became VEB Chemiefaserwerk Friedrich Engels, concentrating on the production of acrylic and polyester fibres such as “Wolpryla 65” and “Grisuten”. After reunification, the plant was privatised and bought over by the Swiss: in 1996, acrylic fibre production was modernised, then a new polyamide plant was commissioned.

However, many other buildings were abandoned and what we saw represents only part of the hectares of derelict buildings which stand along the railway. Without the will to regenerate Premnitz, there is no money to decontaminate the land – so unlike the explosives factory at Bishopton or the former Ciba dye factory in Paisley, it is unlikely a new use will be found for this brownfield site in the short term. At Premnitz, the vestiges of the Eastern Bloc all seem negative.

A different kind of industrial hangover lurks in the hinterland of Saxony-Anhalt. The VEB Rohtabak Werk tobacco factory at Glauzig-Köthen is far removed from the cities of Dessau and Halle. It began life in the 1850’s as a sugar cane refinery, but World War Two changed its destiny. In 1946 its machinery was dismantled and sent to the Soviet Union as war reparations, then the sugar factory was converted into a tobacco fermentation plant by the state-owned Kombinat VEB Tabakfabrik which would run it for the next 40 years.

The company was wound up in 1990 and the tobacco factory closed a few years later. Although small businesses use its outbuildings, the larger buildings lie unused. Inside, there is still storage racking for bales of tobacco, complete tobacco drying kilns, and a dining hall whose walls bear some delicate murals. The tiled hallways are scattered with ephemera from the Communist era: drifts of paperwork, piles of spare parts and a few crumpled cigarette packets.

How would you re-purpose these strange and particular structures? Many date back to pre-Great War, pre-Weimar Imperial Germany but while they stand derelict, they are also outliers of the DDR. They tell you immediately about the continuity of German culture across the tumult of the 20th century, and less directly that much may have already gone, but the final absorption of the East is an ongoing project.

|

|

Read next: Nevis Resort

Read previous: Laurieston: Another Brick in the Wall

Back to January 2015

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.