New Urbanism

13 Jan 2014

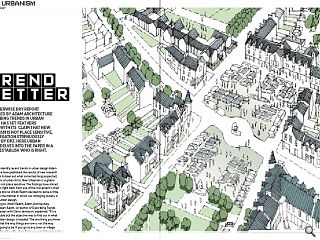

An otherwise dry report compiled by Adam Architecture describing trends in urban design has set feathers flying with its claim that New Urbanism is not place sensitive, an allegation strenuously denied by DPZ. Here Urban Realm delves into the paper in a bid to establish who is right.

Seeking to identify recent trends in urban design Adam Architecture have published the results of new research which seem to bear out what some had long suspected; that in terms of urban form, New Urbanism is a global type that is not place sensitive. The findings have stirred a vociferous fight back from one of the movement’s chief proponents and so Urban Realm decided to delve a little deeper into the manner in which our changing society is impacting urban design.Speaking to Urban Realm, Adam Architecture founder Robert Adam, co-author of Describing Trends in Urban Design with Claire Jamieson, explained: “It’s a bit indigestible but the objective was to find out in what direction urban design is headed. The one thing you know for sure is that the way things are now is not the way things are going to be. If you go to any town or village and you’re familiar with urban form, you can date any part of that pretty much just by looking at the plan. If that was true then, it’s true now and in ten years’ time people will be able to do the same thing.

“Finding trends in urban design is quite difficult because by the time it is built it’s probably ten years after the design. So we decided first of all to have a look at current urban design and see if we could see any patterns. But then we realised there was no accepted methodology for making the comparison purely on a form basis. That’s what instigated the research.”

Drawing on a sample of 350 plans dated between 1990 and 2010, an arbitrary period which the authors concede may not be representative of current practice but which they insist is valid if the descriptive method could be applied to all examples. From there 39 specific descriptive attributes were devised in nine categories ranging from permeability (intensity of connections) to connectedness (the average distance between connections) and density (height and average number of square metres per hectare). Other categories have no comparative measurement but are instead given unambiguous descriptive attributes; namely use, context, block articulation, building articulation, plan type and network articulation.

As far as possible the research is quantitative in nature; for example the methodology for intensity of permeability which Adam measures by intensity of intersection. “As many as possible of the criteria we’ve used are quantitative, you can actually count them”, notes Adam. “In the basic urban grid for instance you have to make a decision based on types and looking at it. If everything is exactly at right angles then that’s easy but if everything is slightly off right angles is that an orthogonal grid or not? You’ve got to make some level of qualitative judgement. They’re not huge but we’ve tried to eliminate all qualitative information if at all possible and keep everything measurable because it’s not about the quality of the end product, it’s about describing the end product.

Of all the samples chosen Adam describes New Urbanism as the only reasonably valid one by testing the difference between New Urbanist plans in North America and elsewhere to tease out any local distinctiveness in the American-originated movement. A sample of 40 plans showed very little difference based on geography. However one, unexpected, outcome was to observe more mixed street patterns outside the US and narrower street patterns in the US. Commenting on this Adam said: “With the Aberdeenshire developments by Urban Design Associates, some of the British people who were working on it noticed the inclusion of things like boulevards which don’t really exist in small Scottish towns. Taking away all the emotion and all the ‘yes, we are, no we aren’t’ we tried a form based descriptive method; nothing to do with architectural style, and ran it. What it showed is that in terms of urban form new urbanism is a global type that is not place sensitive.”

This is an assertion which, naturally enough, causes practitotioners of New Urbanism to bristle, amongst them Andres Duany, co-founder of Duany Plater Zyberk, who cited a number of New Urbanist examples, from Playa Vista in Los Angeles to Chapelton in Aberdeen, to disprove the report. Duany said: “These demonstrate different planning morphologies. There are the two Western American ones, Playa Vista in Los Angeles and Legacy in Dallas, which are rough and ready grids. Another set are the Florida ones of Seaside, Rosemary Beach, Alys Beach, and Windsor. These are rather more formal City Beautiful plans, since Florida was developed (and had its planning heyday) in the 1920s, the best places we have were so influenced.

“Then there are Grandhome and Chapelton. They are among our three Scottish new towns. These are circumstantial and responsive to the landscape--as are many of the more rural places of that ancient landscape. The last set--one in Hertfordshire and one in Edinburgh overcome locational influence as they are a garden village and garden suburb respectively. The morphology is driven by both function and the polemic of growing food socially as the prime determinant.”

Adam remains unwavering however “We chose an equal number of urban plans from North America and around the world. The thing about New Urbanism is that there aren’t that many people doing it. It’s very well publicised and all the work is published and self-identified, so it’s quite easy to get a reasonable sample. My personal view is that new urbanism is one aspect of the most important urban design phenomenon of the moment, which I call contextual urbanism, the idea that urban design is context related. The problem with New Urbanism is that it tends toward formula and dogmatism. It has a thing like the transect, which is turned into a quasi-religion. It publishes absolute principles. It’s also American and Americans have this tendency to believe that the rest of the world is America waiting to happen. These factors tend to make it a more stereotyped version of what is actually a very widespread urban design type.”

Ultimately the merits of New Urbanism won’t be played out in the lecture halls of academia but in the green fields of rural Britain which the movement is steadily colonising. With people voting with their feet (and wallets) in ever greater numbers the semantics of the urbanists are increasingly relevant.

Expert View, Willie Miller, WMUD

This is certainly an interesting piece of work though it will have limited appeal beyond academics, new and traditional urbanists. How many different kinds of turkey are there? Is that the question?

There is a certain superficial sameness in many New Urbanism projects simply because they have developed from the same set of criteria - from regional principles through the neighbourhood to the street and then finally to the building.

It is easy to knock this design process as it seems to eradicate any sort of innovation in favour of a procedure and set of rules which create a certain kind of predefined urban environment.

In fact this very predefined environment is a considerable market success in the US which is why there are so many of them to examine. Some of these projects have been designed expressly around existing landscape features and have benefited greatly from that whether they have incorporated distinctive topography, water courses, old quarries, woodland, individual trees or small ponds.

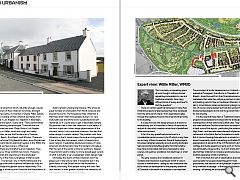

The early evidence from traditional urbanism in Scotland and Knockroon in particular is that it is also a success in market terms - selling out neo-traditional new build mixed use development in the property blackhole of Cumnock in the midst of a recession is no mean feat. The promoters of similar developments in Scotland - for example at Tornagrain, Grandhome or Chapelton of Elswick - know fine well from their financial advisers and marketeers that while they will pay a premium in design and building costs for New or Traditional Urbanism, it will sell, in circumstances where contemporary design may not. Of course volume builder stuff will also sell but these landowner/developers do not wish to go down that route - for now anyway.

It is the case that these New or Traditional Urbanism projects have adopted and worked with the landscape characteristics of their distinctive Scottish sites. They have also used traditional Scottish urban forms as a basis for at least some of the layouts - particularly the widening High Street - and have also taken elements of planned settlements in the North East as foundations to build on. But of course choosing these elements as a basis for design doesn’t necessarily result in something worthwhile. DPZ’s appropriation of elements of the C R Mackintosh’s Artists Cottage and Studio appearing in early work on Tornagrain was particularly cringe-worthy. So it isn’t strictly fair to say that New Urbanism is not place sensitive because the Scottish experience is that it certainly is.

Part of me finds this sort of classification and analysis used by Adam to be quite interesting yet for most practitioners, the decision to have pheasant or partridge is fairly irrelevant as sausage - in the form of volume builder housing - will already be on the plate.

|

|

Read next: Lateral North

Read previous: Look Up Glasgow

Back to January 2014

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.