Ice Lab

23 Oct 2013

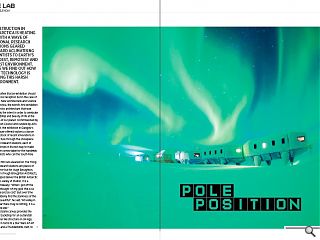

Construction in Antarctica is heating up with a wave of national research stations geared toward aclimatising scientists to Earth’s coldest, remotest and driest environment. Here we find out how new technology is taming this harsh environment.

It’s not often that an exhibition should seek a cool reception but in the case of Ice Lab: New Architecture and Science in Antarctica, the world’s first exhibition of Antarctic architecture, that was precisely the intent in order to celebrate the hardship and beauty of life at the bottom of our planet. Commissioned by the British Council and curated by Arts Catalyst, the exhibition in Glasgow’s Lighthouse offered visitors a chance to take stock of recent innovations in architecture through five showpiece national research stations, each of which strives in its own way to make life more comfortable for the hundreds of scientists who call the South Pole home.For film fans weaned on The Thing arctic research stations are places of cold terror but for Hugh Broughton, director of Hugh Broughton Architects, who helped deliver the British Antarctic Survey’s Halley VI Station, it is a place of beauty: “When I got off the plane I thought ‘oh my god, this is so desolate and so cold’. But over time you suddenly find the starkness of the site so beautiful”, he said. “At Halley in particular there truly is nothing, it is a flat white site.“

This blank canvas provides the perfect backdrop for an outlandish caterpillar like structure on ski legs, likened in turns to a Star Wars AT-AT Walker and a Thunderbirds craft, to be towed away from the dangers of collapsing ice shelves – a fate that has already befallen Halley’s I to V. “People think the modules are tiny, like cars,” noted Broughton, “but they’re actually the size of a standard terraced house and they’re raised 4m to the underside of a module and 10m to the top.

“Each of these modules had to be broken down into kit form because it had to be unloaded from a ship onto sea ice which can fracture quite easily, so we had to break it down into nine ton loads and then put it all back together again. I make it sound quite simple, but it was anything but. It took four years of 10 week summers to do it. It’s a big engineering challenge as well as an architectural challenge. Every season when it was being constructed there were probably 70 builders from Galliford Try there, alongside 30 or 40 from the British Antarctic survey.”

Each of these modules is connected by a super insulated link, like train carriages. These can be unlocked to lower the module down on hydraulic legs before being repositioned using bulldozers or tractors. This came in handy as the research station was required to be built on the site of Halley V as a dormitory for construction workers, before being moved 15km inland. “One of the key requirements for Halley VI was that it should be moveable to prevent it disappearing on an iceberg,” observed Broughton. “That’s one of the reasons why it’s a series of modules, each elevated on a series of skis so that they can be disconnected and pulled inland when there is a risk of it breaking off.”

Commenting on the patriotic colour scheme Broughton said: “The red was a conscious choice but the blue modules were originally green, until the British Antarctic Survey said they already had a lot of green buildings at their other stations. One of their senior people said ‘if you want to win this competition you’re going to need a colour other than green because we have green coming out of our ears’. I know it sounds bizarre built I never clicked on the red, white and blue thing till it was too late. I just liked the colour.”

Researchers can walk from one end of the caterpillar to the other but it’s split in half with a bridge inbetween - so that if there is a fire you can escape from one side to the other and shelter there until rescue. “We looked at different shapes rather than just have it in a straight line”, said Broughton, “but at Halley the wind blows in one direction 95 per cent of the time, so the wind whistles underneath the modules and creates drifts on the leeward side. Having this orientation means you can minimise the time spent in tractors trying to manipulate the snow and ice.”

So what are the likely spill over benefits for the rest of the industry? “It’s a bit like a F1 racing car where elements that were invented for this building can filter down to the regular construction industry and have a significant impact”, states Broughton. “When it’s expensive and difficult to build you have to be very ergonomic and it’s amazing how little space is taken up with bedrooms and how much comfort and storage is built into those spaces. A lot of thought went into how people live and work when there is three months of darkness which obviously has an enormous application to people working in northern Russia, Scandinavia and Canada.”

This is felt from the moment researchers wake up as their alarm clocks include daylight simulation bulbs to suppress melatonin and enhance serotonin production, to give people a bit more bounce at the start of their day. “We also worked with a psychologist to come up with a palette of colours which aided people’s level of activity, whilst improving sign posting within the station and we created spaces where people could be on their own as well as come together as a community,” added Broughton.

“The cladding solutions exceed British building regulations 100 fold in terms of air infiltration which significantly reduces heat loss and heat gain. We used a vacuum drainage system like an airplane but here we managed to reduce water usage at Halley V from 120 litres per person per day to just 20 litres, an eighth of the usage of a normal person in the UK. That may not have much relevance in the driving rain of a Glasgow summer but it does have an enormous relevance to a lot of places where water is scarce.”

Since completion Broughton has been snowed under with requests for assistance and input for similarly extreme builds for governments ranging from Spain to the US, demonstrating the collaborative and international nature of work in the field. With a construction budget of just £26m, Broughton is proud that his scheme came in at ‘half the price of a Chelsea striker!’ Projected to live a productive life of at least 35 years, the station should be a key player in research for a long time to come.

Read next: Fountain Quay

Read previous: Library of Birmingham

Back to October 2013

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.