Speed of Light

11 Oct 2012

The Edinburgh Festival’s most beguiling work of landscape art, speed of light, has wrapped up for another year with a fresh take on audience participation. Here Kenton Wilson, wields his light-staff and discusses the contribution the transformation of Arthur’s Seat into a living light-sculpture has made to Edinburgh’s cultural landscape.

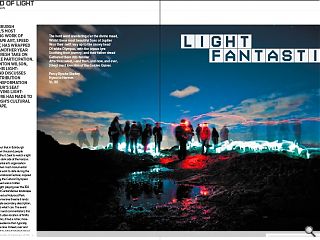

So it came about that in Edinburgh August 2012 ten thousand people travelled to Arthur’s Seat to watch a light show from the dark side of the horizon. The environmental arts organisation NVA created their most monumental and ephemeral work to date during the Edinburgh International Festival, inspired and assisted by the Cultural Olympiad.What ensued was a molten landscape of light, playing over the 350 million year old Carboniferous landscape presently defined as Holyrood Park. Typically for immersive theatre it tends to defy adequate secondary description, though I will do what I can. The event divided viewers and commentators; this being the most urban location of NVA’s large scale works, it had a richer, more cosmopolitan audience than typically tends to be the case. Indeed, over and above the eight hundred ticketed places each evening, scores of members of the public also swarmed to watch from the cheap seats on the hill.

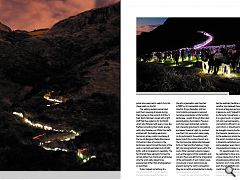

The walking audience ascended past them, pausing at leisure during their journey to the summit of Arthur’s Seat. Each had been issued with a light staff that they relied on for torchlight- which also flickered with every move like fireflies, harvesting their kinetic energy with a tiny Faraday coil. Whilst the staffs emitted soft, fluctuating electronic harmonics at key points (courtesey of the sound designers Radio Resonance Orchestra), tribes of runners in the landscape below formed the body of the work in centrally animated suits of LED lights, with a full spectrum capability. The fact that all these elements formed the canvas rather than the brush emphasises why the work really asked to be experienced rather than photographed or described.

It also marked something of a departure for NVA. If you’re reading this you’re likely already familiar, but the arts organisation was founded in 1992 by its irrepressible creative director, Angus Farquhar, and has most notably pioneered a nuanced narrative presentation of the Scottish landscape- usually through after-dark perambulatory illumination. Previous work has been abstracted, certainly, but inherently grounded in storytelling and place. Speed of Light, by contrast, was their first work which relies solely on its participants; the existing path layout which the runners traced, and the Olympus-like relationship between Arthurs’ Seat and the Salisbury Crags left only topographical traces within the work. Other resonant cultural imagery such as the legend of the Gododdin and volcanic flows was left to the imagination of the participants; if such notions were consciously or even subconsciously present during the work’s conception, they are so subtly embedded as to hardly leave obvious traces at all.

It might be said in fact that therein lies the aesthetic faultline in the work- whether one believed these resonances to be so ambiguous as to pale into irrelevance, and if indeed this matters. As Farquhar himself asks- whether it is a good work, or a great one. Is a rich and nuanced tapestry of synaptic connections sufficient in an abstract work of art, or should particular aspects be brought more to the fore? Leaving the thematic decisions so open-endedly to the audience is a bold decision when the work’s duration and performance is inherently restricted, and as Angus acknowledges, even risks being vacantly misunderstood merely as spectacle.

On several levels it can simply be celebrated to have occurred at a unique intersection of technological, physiological, political and geographical tectonics, and- more profoundly than even the rest of NVA’s own oeuvre- could have occurred at no other time in history. If- as is tentatively planned- Speed of Light goes on to manifest in Glasgow 2014 and Rio 2016, it will be fundamentally a different work, perhaps with its implicit themes of post-industrialisation and choreographed dérive respectively replacing tribal communion as central motifs. But could it have evolved even as an abstract concept elsewhence in the world? To cite but a few, might it have been conceived this way without Donald Dewar or Enric Miralles? Richard Long or Cai Guo-Qiang? The London 2012 Cultural Olympiad or Event Scotland? Almost certainly not; it is in and of its time.

The Legacy Trust’s support for the project was based primarily on the admirable profile it generated for running as sport, especially amongst the notoriously languid arts community. But the lasting impact of Speed of Light for the arts and design sphere is inevitably less demonstrable. When Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty of the K Foundation proclaimed in 1994 to have burnt £1million of their musical royalties on Jura, it was largely derided or ignored- not necessarily because of the validity of the act but because of the difficulty and obscurity of its transcription into the public record. NVA’s influence may be felt over decades in landscape art, but since they are as yet without comparable peers or a more established tradition, the significance of their work relies generously and bravely almost entirely on living memory.

For landscape design NVA’s work is perhaps more relevant than making cosmic landforms- and more significant than carving poetry in stone. The subtlety of the shimmering choreography of lightsuits was certainly inspirational in demonstrating the transmutations possible within a finite network of established pathways, as was the seductive tracing of contours across the hill. For all but the most familiar, ascending Arthur’s Seat in a small personal halo of ground light brought an almost supernatural, sensual intimacy with the micro-topography of the path. The penetration of the walker’s route through the steeply inclined tableau of the runners’ domain in particular spoke vibrantly of point-and-plane Cartesian dynamics, like flying into Las Vegas on a starless night, or a spacecraft ascending through and beyond the Milky Way.

This depth of thought and layering of readings of the landscape is one of the most profound lessons we can take from this work. That multiple stories and histories can be overlaid successfully without confusion, but that it takes hard work and rigour to achieve. That the best design- like all successful forms of management- should ultimately be evident by its apparent invisibility.

For designers seeking to stimulate public (re)engagement with landscape, a nuanced consideration of sensory boundaries can clearly bring powerful results- despite the prevalent trend of legislation. Inspirationally, not least due to an intelligent and careful risk management strategy, Speed of Light tales of septuagenarian runners, the wheelchair athletes and the lower limb amputee who followed the full walking route on crutches may linger longer in the mind than the few apparently more able-bodied walkers who were unable or unwilling to tackle the sometimes difficult terrain in its entirety. Why use textural and aural design in the daily environment solely to assist the sensory impaired? Both can heighten spatial awareness and enjoyment- and materially affect the eventual popularity, usage and safety of a building or public space. The fact that these notions may seem like spurious design considerations merely highlights the aspirational deficiency in our built environments. It really isn’t rocket science.

Returning to the Speed of Light; for a few hours each evening Hermes himself manifested through all of the participants, for a score of nights between the two 2012 London Olympic Games. Guarding the pathways, guiding the transient souls or conveying messages between them, assembling the summit cairn or winging across the hillside. For at least an evening apiece, the ten thousand who attended in Edinburgh were in the mightiest sense, Olympians.

And for that, NVA, we salute you.

|

|

Read next: Westfield Avenue

Read previous: Best Engineers 2012

Back to October 2012

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.