Sculpture

21 Aug 2012

Architects are increasingly coming to embrace sculpture to give life and vitality to their creations, eschewing the so called ‘plonk-it-art’, a term used to denigrate last minute bolt on’s. Here we explore the increasingly fuzzy boundary between sculpture and ornamentation and ask if these are really one and the same thing.

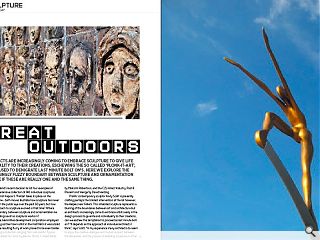

Historic Scotland’s recent decision to list four examples of Glenrothes’ extensive collection of 140 individual sculptures comes as Amish Kapoor’s ‘Pretzel’ takes its place on the London skyline - both moves illustrate how sculpture has never been far from the public eye over the past 50 years but how has our approach to sculpture evolved in that time? Where does the boundary between sculpture and ornamentation lie and can buildings exist as sculptural works in?When the Glenrothes development corporation employed David Harding as their town artist in the mid 1960s it was a bold move, but the resulting flurry of work proved to be even bolder. Encompassing a collection ranging from naturalistic figures such as the B listed ‘Ex Terra’ by Benno Shotz, C listed ‘Birds’ by Malcolm Robertson, and the C(S) listed ‘Industry, Past & Present and ‘Henge’by David Harding.

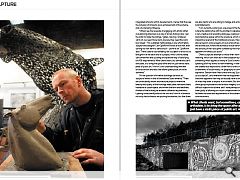

Prolific contemporary sculptor Andy Scott is presently crafting perhaps the boldest intervention of the lot however, the Kelpies near Falkirk. This inhabited sculpture represents a blurring of the boundaries between art and architecture but as architects increasingly come to embrace artists early in the design process to give life and individuality to their creations, can we eschew the temptation to proceed as last minute bolt on? “It depends on the approach of individual architects I think”, says Scott. “In my experience many architects do seem to enjoy the creative dialogue and mutual respect between the disciplines, and the process of enabling sculpture or other integrated artworks within developments. I sense that they see the inclusion of artworks as an enhancement of the scheme, and a humanising influence.

“Others see the requisite of engaging with artists (often as a planning directive) as a way of simply ticking a box: ‘get the artist to make the railings / gates / paving / whatever, call it art, we need those items anyway, they need the work: box ticked.’” This outdated methodology is one which fellow sculptor and designer Colin Spofforth knows all too well, even coining his own term to denounce it - ‘plonk-it art’. Spofforth said: “There used to be a tendency for a sculptor or artist to be brought in at the back end of a project, which unfortunately can sometimes end up being an expensive way of satisfying the 106 requirements! What clients want, but sometimes can’t articulate, is to bring the space alive and not just have a static piece of public art. I think it’s this understanding between an artist and an architect that allows great public art to be delivered.”

On the question of whether buildings can exist as sculptural works in and of themselves Scott remarks: “There are undoubtedly recent architectural projects where the beauty and quality of the buildings really does transcend basic habitable or usable space, and where the form and aesthetic finishes of the building far exceeds utilitarian requirements. Lighting undoubtedly adds to the mix and I think it is fantastic not only that architects are pushing boundaries, but that there are also clients who are willing to indulge and embrace such bold statements.

“I am currently working on one project [The Kelpies] where the relationship with the architect is developing into a very creative and rewarding dialogue, creating a habitable and interactive space within the sculpture, which is a very interesting reversal of the traditional process. However I’ve also sensed on some projects an aura of aloofness around the architecture, where the architects would rather not have the sanctity of their discipline cluttered by the imposition of apparent frivolities such as art.”

Often sculptures attempt to imbue their work with meaning, which can often aid in their adoption by locals, something which applies to many of Scott’s works: “Personally speaking all of my works do have meaning, in that they are created as a response to a brief from a client: this may be elements of social history, or geography or community aspiration. Seldom have I had clients who say “just design us a sculpture”...and whenever that has happened it quickly becomes apparent that they do actually have a strong idea of what they want or expect in an artwork. But the balance of client group expectations and artistic integrity is often a very difficult objective to achieve, and I have perhaps occasionally been guilty of allowing too much compromise in artworks to facilitate the taste and requirements of the stakeholders and commissioners.

But what makes good sculpture, must it have meaning? Harding told Urban Realm: “In the thirties Mies commissioned a Maill sculpture for his pavilion so that the organic form of the sculpture ‘relieved’ and played well against the formalism of his building he set a trend that carried on into the 60s and 70s. I used to teach my students that that ‘formula’ - the sculpture as counterpoint to the building (sometimes even rescuing the building) - was redundant and that they would find more exciting and stimulating opportunities if they saw their work in terms of art and the city, the urbs, and not simply as art and architecture.

“The latter often resulted in design and decorative works. Many of today’s ‘signature’ buildings are sculptural in themselves and have no need for artists though whether those buildings carry ‘meaning’ I’m not sure.”

Scott adds: “I am sure you would get a different answer to that question from every sculptor or architect you asked. For me it is about narrative, iconography, place-making and engagement. I work almost exclusively in the public realm as I enjoy the challenges of the widest possible audience. The challenge for me is to instil a degree of intellectual rigour which may or may not be immediately apparent. I have had numerous unexpected and humbling accolades and experiences through the course of my works. I’ve had vociferous critics turn around their opinions completely, and of course one or two become more entrenched and bitter. I guess then it could be said that it evokes responses which show people’s true natures.

“That is a story I also know to be true of a great number of architects, and in that respect I believe the disciplines have much in common. No-one ever knows the rigours and trials that most architects go through and the compromises of ‘cost engineering’ which result in buildings which may well be functional, but are by no means striking pieces of architecture. The same unfortunately sometimes applies to the process of public art production.”

Sculptural work can be said to serve a purpose beyond its aesthetic appeal with Scott observing that many of his own creations have been swiftly adopted by the communities in which they sit, both as local landmarks and sources of local pride. In today’s chastened economic environment some have labelled sculpture as frivolous but it is a charge that Scott vehemently denies: “As a professional sculptor who works 60 - 70 hour weeks, I’m not likely to think of my discipline as frivolous. Since man could first scratch marks on a cave wall or push lumps of clay together he has been driven to create and adorn his environments, so I regard public art as something altogether more primal and life enhancing.

“When times are tight the spirit is most in need of elevation. We live in peculiar times of fiscal philistinism. The arts (all of the arts) are a soft target for naysayers and such bastions of moral propriety as the Taxpayer’s Alliance. If they put as much effort into highlighting the blight of tax avoidance by big business, Britain would be a very different place. I can only refer to numerous personal accolades and notes of praise for my works which assure me that it is worth it... but then I would say that. “

An increasingly competitive market is seeing growing numbers of landscape architects bidding for sculptural work - on the grounds that some paving or lighting is involved, and architects undertaking arts based projects now that the construction industry has dried up. Scott is keen to stress the interplay between the professions, noting that public art is a valuable and often very valuable contract for a range of engineers, lighting designers, electrical contractors, haulage contractors, crane operators, galvanizing and specialist fabricators, and very often architects, all of whom “do a turn” from big commissions. Scott stressed: “The trickle-down economic effect as well as the aesthetic or spiritual benefit is surely worth recognising. There is a myth, which I’ve seen on Urban Realm’s blog, that the artist pockets the budget and these things magically appear... if only.”

Perhaps ultimately the gap between sculptors and architects really isn’t as great as it may at first appear? Scott disagrees: “I don’t think so, but again that’s a personal thing. As a teenager I was accepted to study architecture, but opted for fine art at GSA.I know many architects who applied for art school, but opted for architecture. I married an architect and many of my closest friends are architects. I think there is considerable overlap in a desire to enhance the built environment, to elevate the mundane, and to contribute to society through our skills and knowledge. As disciplines we both deal with the materials and experiences of the urban realm, and deal with the pitfalls and rewards of dealing with the public.”

Spofforth on the other hand was first drawn to sculptures by their sense of permanency, striking out in life initially as a graphic designer before changing tack after finding it to be superficial, preferring instead the permanency of sculpture. That permanency carries dangers of its own however, immortalising any mistakes that may slip the net. Some egregious contemporary examples, notably Tom Church’s depiction of Mel Gibson’s Braveheart persona - subject to regular vandalism by an irate public it eventually prompted flustered officials to build a security fence before giving up and removing it in 2008.

As in all disciplines responsibility ultimately percolates up to the client pulling the purse strings as Scott evinces: “As in architecture it is the enlightened client, the willing commissioner and the inspiring location which result in the strongest works and those are the projects that keep sculptor and architect alike fighting the next round.”

In sculpture as in architecture good design flourishes best when all parties party to it are willing to take risks. No easy task in today’s risk averse climate but one which is perhaps more important than ever.

|

|

Read next: Water & Drainage

Read previous: Brymbo Steelworks

Back to August 2012

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.