Handyman

31 Oct 2011

In contrast to how early ships were made, Hadid’s museum could not have been constructed without computer and advanced 3d modelling systems. The outcome may have been an easier creation and construction of a complex architectural form, but the loss of a craft process, in my opinion offers less interest as a result.

A few weeks ago I visited an extraordinary exhibition, which closed on the 14th of August; “Drawing on Riverside” by Patricia Cain. Cain is an artist who was a lawyer not an architect yet her paintings and drawings of the construction of Zaha Hadid’s Riverside Museum have, in my opinion, been the best outcome from that project.Cain’s work displays exceptional analytical skill and draughtsmanship and her exhibition also featured prints and drawings from great Glasgow artists from the turn of the century, including Muirhead Bone and William Simpson who also drew inspiration from the river Clyde, shipbuilding and the architecture of the city.

Cleverly threaded through the paintings and artwork were physical models and displays, the most remarkable of which was the scale model of the hull of a ship, constructed by Cain and Ann Nisbet specially for the exhibition and made in the gallery. An achievement in itself, but done for a specific purpose; to understand and record the intricacies involved in the making of a ship and to compare that craft process with the computer assisted construction of the new riverside museum.

It reminded me that Glasgow was once the foremost ship building city on earth and that this eminence was predicated, among other things, on the quality of design and craftsmanship, including hand drawing. Historically, as part of shipbuilding, full size drawings and details were sketched out in huge warehouse buildings along the riverfront, moulds made and hulls constructed from the templates that were produced from these drawings. This was a complex and rigorous process that demanded extraordinary draughtsmanship and engineering skills.

At Cain’s exhibition, the development of the ship from initial drawing of the shape, the construction of the formwork to the later built stages were detailed in almost forensic fashion. Cain explained the process and complex engineering without reliance on computer or modelling programmes.

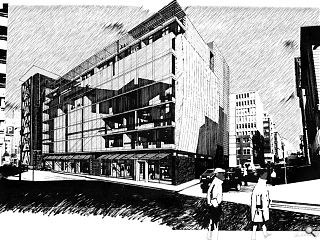

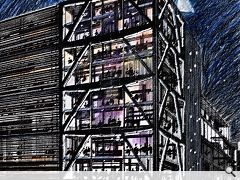

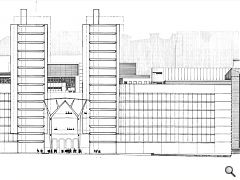

As the exhibition was closing its main subject was opening- Glasgow’s newest architectural “icon”; The Riverside Museum by architect Zaha Hadid. In contrast to how early ships were made, Hadid’s museum could not have been constructed without computer and advanced 3d modelling systems. The outcome may have been an easier creation and construction of a complex architectural form, but the loss of a craft process, in my opinion offers less interest as a result.

Like the ship in her exhibition, Cain analysed the museum as it grew out of the ground and studied the development as almost “artist in residence”. After five years of study she became intimate with the building’s construction, engineering and form and she has been able to record with characteristic clarity the historic phases of its development.

It seems to me that the Glasgow’s ship designers and builders at the turn of the century shared Patricia Cain’s understanding and respect for form, engineering and beauty. In the 21st century complex computer programmes and 3d technology has “advanced” architecture and engineering, to allow architects to achieve any form the computer model has the capacity to predict but this influence has robbed a number of architectural structures of their integrity and resulted in less satisfying outcomes. The process of understanding how to make a complex shape seems removed from human hands with architects and engineers subordinate rather than instrumental to the development and output of design.

Recently I was invited to lecture and critique the work of Dessau Bauhaus students in Germany. I sat through numerous, glossy presentations, where the emphasis was on imagery and the production of sketch up and architectural graphics. I was disappointed by the absence of any fundamental, bone deep understanding of how to make a building. When I suggested to one student that his work looked good but lacked rigour and analytical depth and asked if he knew how to construct his project, he replied that such knowledge was not needed in architecture today. When qualified, he’d simply pass his “concept” on to a technician to make it a reality, no doubt using advanced computer modelling . His tutors nodded in agreement.

For those of us who produce pencil, pen and ink drawings and sketches as a basis for our architecture the student’s admission and general acceptance is saddening. My trust in hand drawing has increased over time in the face of ubiquitous 3D computer graphics. I remain bewildered by the reluctance of some students and practitioners to hand draw for I agree with Robert McCarter that “the hand-drawing is the place, where thinking and making are joined together...” I believe the act of drawing by hand is fundamental to development of a real understanding of how architecture is made. It is a means to consolidate thinking on practical issues for the building, where light will be, what should be solid or void and most importantly, how the idea can be given form in the built sense.

"The Thinking Hand" by the Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa is now seen on many architects’ bookshelves. Pallasmaa is a talented architect with a strong reputation and though many of his words have been lost in translation his essential message of "draw, don't think" is very important. My understanding of his meaning is that drawing facilitates creativity and frees the mind.

Unfortunately, few working architects now have the confidence, skill or aptitude to use pencil and paper and have distanced themselves from the creative act. Many designers have little authentic contact with the development process and usually it shows. The default mode in some offices is for working drawings to be developed from concept on- screen or delivered fully formed through computer 3D modelling which generates images of photographic quality that pass for originality and rigour.

Hand drawing has intrinsic value. It should be an effort of artistic production. The output of the great architectural draughtsmen, Paul Rudolph, Wilhelm Wohlert, Frank Lloyd Wright and Mackintosh, have specific distinction and style that attests to the quality of their thinking as well as their artistic capacity. Their drawings have become iconoclastic because of the duality of their creative approach and their work is clear testimony that no effort in preparatory analysis is wasted. Through hand drawing you can learn everything about the architect, the degree of rigour and research that they bring to their projects, their attitudes and their sensitivity. It is no overstatement to suggest that hand drawing represents the stain of the true architect’s soul on paper.

There is no doubt that computer assisted design and 3D modelling has its place but my earnest view is that this place should be ancillary to and supportive of the true artistry involved in the drawing and development of a building by hand.

Professor Alan Dunlop

FRSA FRIAS

|

|

Read next: Navel Gazing

Read previous: Cartoon Cavalcade

Back to October 2011

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.