New Schools for Glasgow

17 Apr 2007

Glasgow is currently bucking the trend, avoiding PPP procurement, using traditional contracts and running design competitions for its new schools. Prospect publishes the winner and shortlisted entries for the city’s latest competition to find an architect for Hillhead Primary.

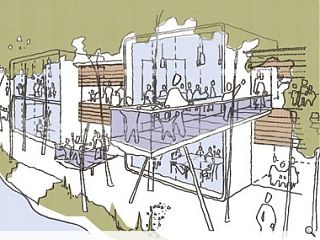

Not since Hampshire County Council in the 1970s has a local government education department been able to deliver schools without provoking criticism among architects. Today, Glasgow City Council is provoking considerable parental opposition as it tries to rationalise its existing school provision. However, Steven Purcell, the council leader, has made a huge commitment to education and it seems somehow appropriate that the city has chosen to build the next round of primary schools using traditional procurement rather than PPP. At the end of the 1990s, Glasgow was one of the first in Scotland to embark on a large PPP school-building programme. Regardless of whether PPP can be seen as a good use of public money, the quality of the environment, although an improvement on what went before, was poor and the buildings were little more than sheds. Today five new schools are being built under traditional contracts. The question that must be raised is whether this results in a more expensive product and or a better-designed product. The city is in the process of building 16 new schools – 11 will be delivered by Building Services, which has now been rebranded and transformed into an arms-length organisation called City Building Group. Five schools are being procured through design consultants. A new non-denominational school at Hillhead will bring together children form Dowanhill, Hillhead, Kelvinhaugh and Willowbank primary schools and two nurseries. In December last year, ABC architects were appointed to carry out the design work on the three schools. A strong component of ABC’s winning bid was a commitment to the idea that schools, as important local institutions, should perform a role within the community as a whole, both as a resource and as civic buildings. “We always aim to look outside the narrowest ‘architectural’ interpretation of our role,” says Bruce Brebner, a partner at ABC. “We recognise that architects are uniquely able to shape the ‘character’ of an area and therefore contribute to its success or failure. We are committed to the design of places which present a feeling of their ‘own identity’.” In February this year, jm architects won the commission to design Hillhead. Hillhead is particularly controversial for a number of reasons – high property values and the university and the BBC in the area mean residents tend to be middle-class, so parents are likely to play a very active role in the consultation as are local conservation enthusiasts. Six practices were shortlisted for the competition and were assessed on the basis of design quality and fee tender. The competition was to assess the competence of the architect and to identify the right architect for the job. The architect was selected using a scoring matrix at the end of which all of the scores are added up. The judging panel was made up of professionals from the council. The fees bid for Hillhead ranged between £907,687 and £1,616,150. The winning scheme appears to have also been the lowest bid. Now that an architect has been appointed, the council must begin its consultation process. It is a tailored process, the character of which depends on parental interest. There are often issues of denomination and special needs, but at Hillhead the crucial issues will be conservation and the park. Although the new schools will be built using traditional procurement, the council has developed a novel way of controlling costs by lumping the design teams’ fees together and getting the architect to carry the entire financial risk by subcontracting the other consultants. Despite the reservations participants in the competition may have had about the process, they all clearly thrived on the opportunity to compete. “We commend the city council on holding a limited competition,” says Douglas Roxburgh of HLM. “It means that the commissioning body is interested in quality, not just in how much it costs.” Changes in population and catchments, and the growth of parental choice in school placements have created a range of challenging issues for designers of primary schools. For each school, there are different issues – some are crammed, while others are seriously under occupied – but most seem to be overburdened with directives such as Every Child Matters, extended schools, healthy eating, walk-to-school initiatives, inclusion policies for children with special educational needs, and eco-schools. And then, of course, there’s the Scottish Executive’s Parental Involvement Bill. The brief for the Hillhead competition was a very weighty – it will later form the contract for the design team. The new school is quite a big primary. It has a roll of about 700, with an intake of three new classes each year. The new school will be located on a long and narrow site. The northern portion on Gibson Street is clearly part of the built structure of the West End, but the south relates to Kelvingrove Park. Outdoor classrooms, extendability and flexibility are all important were important aspects of the brief. The assessors were also keen to see a sustainability approach. “The best schemes are those that keep all of the balls in the air, that can create a safe teaching environment, that are economically viable and can be built within the council’s sustainable construction policy,” said a council spokesperson. Everyone who participated in the competition seems to lament the fact that they didn’t get a chance to talk directly to the users. From the client’s point of view, it’s clearly better not to deal with too many variables. Once an architect is appointed, the consultation process can begin. In reality, solutions will only really develop once that relationship is established. Which is why the council is very keen to stress that the competition process was about selecting an architect. The final scheme could bear no relationship to the competition submission. competition winners: jm architects Architect: jm architects The winning scheme proposes placing the building away from Gibson Street. The jm architects proposal was to form an urban park on the main street, placing the entrance at the point where the site narrows. The classrooms are organised in an informal way along a central internal street, and the entire building is covered by a large, over-sailing roof. On the south side, two storeys of classrooms overlook the river Kelvin, to the north is a linear protected playground. The school has a separate games and dining room that could be opened to form a bigger assembly space. Architect: Gm+ad Gm+ad presented three different proposals: a school in the park, a campus school and an urban building. The architects were keen to deal with the complexity of the site, the issue of access (they considered a dropping off point for children on Kelvin Way), and the engagement of both the local community and conservationists. All three options had a simple plan, but in the park option, the strong urban forms were broken down to establish a more diffused relationship with the landscape. Based on their experience at Hazelwood – a school for blind and deaf children currently under construction – the architects tried to make the planning as legible as possible, so that it was clear how you should move around the school by clearly defined routes and key markers. The views up and out of the site to the key neighbouring buildings was an important consideration. Architect: Anderson Bell Christie ABC’s proposal addresses both the park and the city – the school is seen as a key community building reinforcing the urban structure. It is designed to be welcoming and friendly, as well as secure. The nursery, library, sports facilities and a parents’ cafe are accessed off a new square on Gibson Street. There is direct access to the playground from the classrooms, which each have a different character giving a feeling of informality. The classrooms are configured to provide a sunny, safe play courtyard which is envisaged as an extension of the assembly space. The external space will be diverse, with the maximum potential for pupil involvement in its design both now and in the future. Architect: HLM In the HLM proposal, the school is set away from the street, and the communal facilities are placed on three levels on the urban edge on Gibson Street. HLM was concerned to involve all of the stakeholders in the process. There are clusters of classrooms for each year group, scattered along the edge of the water “like pebbles on the riverbank” and linked by a common internal ‘street’. The design allowed for plenty of natural light, but HLM was keen to avoid direct sunlight, particularly in the middle of the day as its experience suggests it creates a poor classroom environment and a demand for mechanical cooling. The building has a green roof and outdoor learning spaces. Architect: BDP BDP took a careful look at the brief and outlined the possibility for an urban school and a school in the park. It developed the later scheme and suggested that the Land Services facilities on the site should be moved elsewhere, and the street frontage on to Gibson Street should be sold in order to allow the development of tenement-style housing and to generate revenue. In the School in the Park scheme, it proposed a three or four-storey building in which the nursery was located at the entrance to the school, and a safe play area was created away from the River Kelvin. Architect: DSDHA DSDHA is a London-based practice with a good track record of producing buildings for young children. The practice supplied three design options, all of which created a simple three-storey building placed towards the back of the site, but still addressing both the street and the garden. On Gibson Street, it placed a separate low-rise nursery building. The classrooms are organised in clusters and open onto canopied play spaces. DSDHA stressed the character of its approach, which is to collaborate with the end user rather than developing the detail of its proposals.Read next: StudioKAP in Balfron

Read previous: Public private partnerships: the devil or the deep blue sea

Back to April 2007

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.